| County |

Parish |

Comment |

| ANTRIM |

Ahoghill |

Rootsireland lists baptisms from 1844 but they actually start in 1864. Elsewhere baptisms are recorded from 1833. |

|

Ballymoney |

Rootsireland has eight years of marriages not found elsewhere. |

| ARMAGH |

Ballymacnab |

Rootsireland has 25 years of early baptisms missed by NLI |

|

Derrynoose |

Rootsireland has 17 years of early baptisms missed by NLI |

| CAVAN |

Moybologue |

The earliest NLI baptismal register is 40 years before the Rootsireland transcript |

| CORK |

Aghada |

Rootsireland has an 18th-century baptismal register missed by NLI |

|

Glounthane |

The local parish has records almost 50 years earlier than NLI |

|

Newmarket |

NLI has 13 years of early baptisms missing from Rootsireland |

|

Shandrum |

Rootsireland has two 18th-century registers missed by NLI |

|

Cork city: St. Mary’s |

The only transcripts are by Ancestry and FindMyPast from NLI microfilm |

| DONEGAL |

Kilbarron |

NLI has 5 years of early baptisms missed by the LDS and Rootsireland |

| DUBLIN |

Artane, Coolock, Clontarf, Santry |

No NLI microfilm. Rootsireland from 1777 |

|

Ballybrack |

No NLI microfilm. Rootsireland baptisms from 1841 |

|

Bohernabreena |

No NLI microfilm. IrishGenealogy baptisms from 1868 |

|

Dublin city: St. Michael and John’s |

Earlier baptism register on IrishGenealogy |

|

Naul |

No NLI microfilm. Rootsireland records from 1832 |

|

Sandyford |

Earlier baptismal register on IrishGenealogy |

| GALWAY |

Cappataggle |

Rootsireland has an 18th-century baptismal register missed by NLI |

|

St. Nicholas (Galway city) |

NLI has 17th and 18th-century fragments missed by Roostireland |

|

Killascobe |

Rootsireland (and the LDS) have a very early fragmentary register missed by NLI |

|

Loughrea |

Rootsireland has an early baptismal register missed by NLI |

|

Moycullen |

NLI has 4 early baptismal and marriage registers missed by Rootsireland |

|

Rahoon |

Rootsireland has an early baptismal register missed by NLI |

| KERRY |

Killorglin |

No NLI microfilm. Transcribed from 1798 on IrishGenealogy. |

|

Dingle |

Baptisms 1828-1837 missing from IrishGenealogy, covered by NLI |

|

Moyvane |

25 years of early baptism and marriage records on IrishGenealogy, missing from NLI |

|

Sneem |

Early baptism and marriage records on IrishGenealogy, missing from NLI |

| KILDARE |

Athy |

Rootsireland has an 18th-century baptismal register missed by NLI |

|

Ballymore Eustace |

NLI has an earlier baptismal register |

|

Clane (Rathcoffey) |

NLI has several earlier registers than Rootsireland |

|

Kill |

Several early registers on Rootsireland (and Ancestry) not covered by NLI |

| KILKENNY |

Ballycallan |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Graignamanagh |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Kilkenny city: St. John’s |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Kilmacow |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Mullinavat |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Galmoy |

Earlier baptismal register on NLI |

| LAOIS (QUEEN’S) |

Mayo and Doonane |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

| LEITRIM |

Bornacoola |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Kiltoghart |

Rootsireland include records of Kiltoghart-Murhan missing from NLI |

|

Oughteragh |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

| LIMERICK |

Bruff, Grange and Gilnogra |

Rootsireland has an 18th-century baptismal register missed by NLI |

|

Feenagh |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Limerick city: St. Patrick’s |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Monagea |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

| LONDONDERRY |

Ballinascreen (Draperstown) |

NLI has 2 early baptism and marriage registers missed by PRONI and Rootsireland |

|

Tamlaghtard |

Rootsireland has an early baptismal register missed by NLI |

| LOUTH |

Dunleer |

Much earlier baptismal registers on Rootsireland |

|

Togher |

Rootsireland includes baptisms and marriages 1829-1868 missing from NLI |

| MAYO |

Backs |

Several early registers on Rootsireland (and Ancestry) not covered by NLI |

|

Ballycastle |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Burrishoole |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Crossboyne and Taugheen |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Kilbeagh |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Kilcommon Erris |

No NLI microfilm. Transcribed from 1860 on Rootsireland |

|

Kilvine |

No NLI microfilm. Transcribed from 1870 on Rootsireland |

|

Tourmakeady |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

| MEATH |

Donymore (Curraha) |

Earlier baptismal register on NLI |

|

Kildalkey |

No NLI microfilm. Transcribed from 1782 on Rootsireland |

| MONAGHAN |

Donaghmoyne |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Killanny |

Earlier baptismal register on NLI |

| OFFALY |

Aghancon |

Much earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Lusmagh |

Earlier baptismal fragment on NLI |

|

Tullamore |

Earlier baptismal fragment on NLI |

| ROSCOMMON |

Oran |

No NLI microfilm. Rootsireland from 1865 |

|

Roscommon and Kilteevan |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

| SLIGO |

Castleconnor |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Geevagh |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Sligo: St. John’s |

Earlier baptismal, marriage and burial registers on Rootsireland |

| TYRONE |

Dungannon |

Rootsireland has an early baptismal register missed by NLI |

| WATERFORD |

Aglish |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Ardmore |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Clonmel: Ss Peter and Paul |

NLI has earlier marriage registers |

|

Killea |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Modeligo |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

|

Stradbally |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland |

|

Waterford city: Ballybricken |

Earlier marriage register on Rootsireland |

|

Waterford city: St. John’s |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on NLI |

|

Waterford city: St. Patrick’s and St. Olaf’s |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers on Rootsireland |

| WESTMEATH |

Nougheval |

No NLI microfilm. Rootsireland from 1857 |

| WICKLOW |

Arklow |

Earlier baptismal fragment on NLI |

|

Blessington |

Earlier baptismal and marriage registers at Rootsireland |

|

Roundwood |

Earlier baptismal register on Rootsireland. Earlier marriage register on NLI |

|

|

|

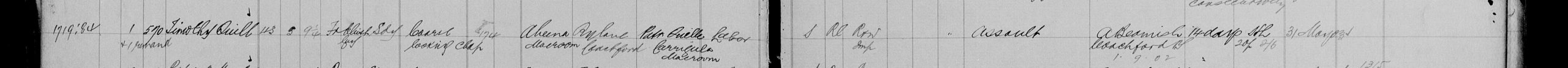

The teacher demands, in English: “Phwat is yer nam?” The response, in Irish, begins: “Bonaparte, son of Michelangelo, son of Peter, son of Owen, son of Thomas’s Sarah, grand-daughter of John’s Mary, grand-daughter of James, son of Dermot.” Whereupon the teacher calls him to the front of the class, hits him over the head with an oar and screams: “Yer nam is Jams O’Donnell!”

The teacher demands, in English: “Phwat is yer nam?” The response, in Irish, begins: “Bonaparte, son of Michelangelo, son of Peter, son of Owen, son of Thomas’s Sarah, grand-daughter of John’s Mary, grand-daughter of James, son of Dermot.” Whereupon the teacher calls him to the front of the class, hits him over the head with an oar and screams: “Yer nam is Jams O’Donnell!”