After Independence, official Ireland understandably set about undoing the grievous distortions wrought on Gaelic surnames by English-speaking administrators. Every surname now had to have an official Irish-language school version, on the basis that we were all Gaels and had had our original names stolen from us.

For the purposes of officialdom, my father became Mac Grenacháin; when I went to school, I became O’Grianáin; my son was later dubbed Ó Gréacháin.

Never mind the tunnel view of history and the hair-raising presumption that Ireland was racially pure, the implicit understanding of surnames was simply nonsensical.

Because the most important fact about all surnames is that they are words. They don’t have DNA, go to any particular church, salute flags, vote or fight. They simply swim in the ever-changing sea of language, evolving as all languages do under the pressure of accents, education, fashion, politics, economics.

For example, the American pronunciation of the surnames Cahill (“KAY-hill”) and Mahony (Ma-OWN-ey) often has Irish people sniggering up their sleeves. But these pronunciations are much closer to the original Irish-language versions of the names (Ó CATHmhaoil, Mac MaTHÚNa). The fork in culture between Irish-America and Ireland preserved something over there that we over here have anglicised more thoroughly.

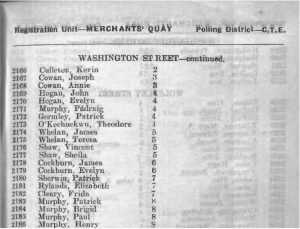

Whether American or British, the language Irish surnames have swum in for almost two centuries is English. Seen in this light, the 20th-century Gaelicisation of surnames, the great wave of adoptions of O’s and Mc’s, was not the reclamation of something lost but a further evolution, a flawed reinvention of an imagined past – ask Theodore O’Kechuckwu, living at 1 Washington Street in Dublin in 1949.

The evolution of surnames has not stopped, though it has slowed, not just in Ireland but throughout the developed world. Mass literacy and computer technology have make it more difficult for change to occur – simply seeing your name in print on a computer screen every day lends it apparent permanence.

Apparent only: I have no doubt that in a few centuries people will look back in amusement at our qnt srnm spllngs.