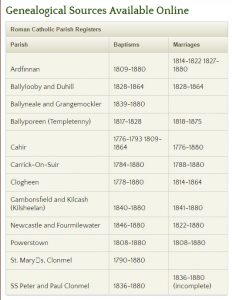

I’ve just spent the last ten days revising and updating my listing of the Catholic registers online at rootsireland and it’s an experience I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy: hour after hour of grinding through mismatched parish names and record dates, testing the ones that look dodgy, amending, adding, correcting … argh.

Still, it was long overdue – rootsireland is by a mile the most useful site for early Irish church records. I’ve been doing piecemeal updates to the listing for the past twenty years, as new records were covered or came online, but never a full-scale run-through. And it was worth the pain, because I learnt a lot.

First, it’s clear that a lot of fresh transcription work is going on in the heritage centres, Or at least some of the heritage centres. For some areas the transcriptions are now well into the first quarter of the twentieth century, and for others nothing has changed in twenty years.

‘Twas ever thus. The good centres have always been very very good and the bad ones horrid. It’s just that some of the horrid are now good and vice versa. (No names, just for now).

A surprising number of recent transcripts end in 1880. This is the cut-off of the National Library microfilms and the implication is clear: those transcripts are from the (sometimes godawful) films. Which means that rootsireland’s advantage over the Ancestry.com/FindMyPast transcripts – copying directly from the originals – doesn’t exist for those transcripts.

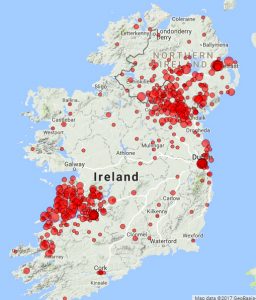

Fortunately, these are only a small minority. More often, rootsireland actually has registers missed by NLI – Sligo, Roscommon, Carrick-on-Shannon … And one of the central axioms of Irish genealogy is thus confirmed: no generalisation about Irish records is true, including this one.

The rootsireland listings themselves can be deeply peculiar. In some parts of the country, records that used to be online seem to have vanished. In other parts, centres seem to be keeping a wary eye on the Church’s recently-enunciated ban on making public any records less than 100 years old. In most cases, centres with online records later than the offending date have simply amended the public listing to conform, but left the actual records searchable. Waterford, in particular, has solved the difficulty of having some records going up to the 1950s by just hiding all its finish dates. An Irish solution to an Irish problem.

And there are many other idiosyncrasies. Wicklow has a fine collection of burial records, both Catholic and C of I. Not a one is online. And many centres have mis-listed their own records, with the wrong dates listed or entire parishes missing.

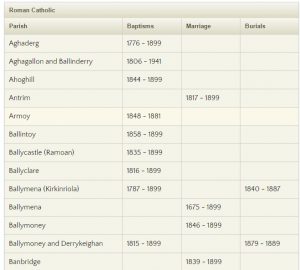

Strangely, because the Ulster Historical Foundation is a seriously scholarly outfit, by far the least reliable listings are for Antrim and Down. Whatever the UHF listing might say, there are no Catholic baptismal registers anywhere on the planet for Aghagallon before 1828, or Ballymoney before 1853 or Ballyclare before 1869. I suspect a longstanding oversight, but it needs some serious attention.

I ran into Bernadette Marks,the doyenne of the Swords Heritage Centre recently and she reminded me of how unkind I’d been about the centres in the past. I reminded her of how I’d changed my tune. But really it’s still carp carp carp, Mr Grenham.

So be on your guard about what it is you’re actually searching on the site. Or just look at the (Updated! Free!) listings.

And if you see any mistakes, please let me know. All carps gladly received.