For a long time, rootsireland had a very bad reputation among Irish family historians. It was impossibly expensive and seemed designed to restrict research access to the absolute minimum. Small wonder that a cottage industry sprang up devoted to ways of extracting information from the site without paying.

As a result, vitriolic criticism of the site is still very easy to find online.

The problem is that it’s no longer justified. Over the past eighteen months, the site has been transformed out of all recognition, guided by what looks like a very good understanding of research and researchers.

First, the clunky pay-per-view unit-based subscription is gone. Now the site offers the online standard, time-based subscriptions, ranging from a year for €225, to (stock up on the black coffee) €10 for 24 hours. Instead of zeroing in on just a few important records, you can now range up and down collateral branches, picking up the kind of secondary information that sheds important sidelights on a family.

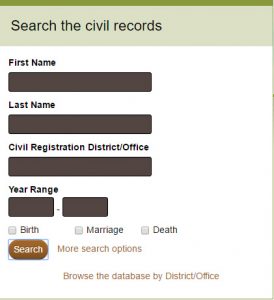

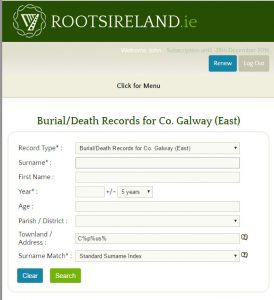

And it’s much, much easier to search. The number of obligatory search fields has been slashed. It’s no longer necessary to enter dates, making it possible to retrieve every single record for a surname (and variants) from every record-set on the site in one go: trawl broad, then winnow.

In some circumstances, it’s not even necessary to enter a surname. When in one of the county sections, you can retrieve every record that lists a particular townland or address, irrespective of the family it records. And you can use wild-cards (“%” not “*”) to do that. So it’s possible, for example, to extract every death in a particular townland between 1864 and 1920, or to find place-names that were ignored by the Ordnance Survey but are recorded in rootsireland’s early baptismal registers.

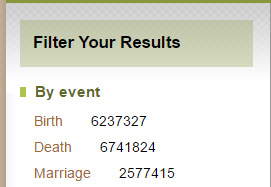

The range of records on the site also continues to expand – it looks as if the threat to its effective monopoly from Ancestry and FindMyPast has galvanised it into action. There are still black spots – Fermanagh, Clare, Wexford, those pesky missing thirteen Catholic parishes in East Galway – but the areas that are good are very, very good indeed. And the chance to test the quality of the Catholic transcripts against Ancestry and FindMyPast has seen rootsireland win again and again.

Even the recent addition of the General Register Office record images to IrishGenealogy has only boosted the usefulness of rootsireland’s database transcripts of local registrars’ records: they are two different records of the same events, each with its own mistakes, but each different to the other’s mistakes. And rootsireland’s version is a searchable full(ish) transcript, not just a name index.

Of course, there are still many flaws. The forename search doesn’t use variants, so searching for a Bridget won’t find you a Brigid. There are undocumented holes in some collections, and unlisted records in others – west Galway appears to have the civil marriages for most of its areas online, for example, but they’re not in the sources-list.

The practice of filling in the county on their map when they have any records at all online is also deeply misleading: Clare appears identical to Sligo, when Sligo has completed almost everything but Clare has just seven sets of baptismal registers.

And above all, there is no library subscription, an option that would democratise access for the many people who just can’t afford their full prices.

Still, no Irish genealogy site is without its flaws.

I’ve never been a booster of rootsireland. In fact, for a long time they saw me as one of their chief tormentors. Now, though, if I’m asked what’s the one essential commercial genealogy site for Irish research, the answer is rootsireland.