For Irish researchers, the five stages of New Source Syndrome are:

- Disbelief – “What? After 30 years of fumbling around in the dark, someone’s just turned on the light? It can’t be true.”

- Unrestrained joy – “Calloo Callay, o frabjous day! Life will be wonderful from now on! The ancestors of every Irish person everywhere will be findable forever!”

- Mild questioning – “The transcriptions seem a bit flawed. Ah well, nothing’s perfect.”

- Exasperation – “For God’s sake, a simple Forward/Back button isn’t too much to ask.”

- Thundering, red-in-the face ingratitude: “They’ve left out Principal Registry Wills, 1891, G-M! How could they, the blithering idiots?”.

As you may gather, I’m at stage 5, and they did leave out Principal Registry Wills, 1891, G-M.

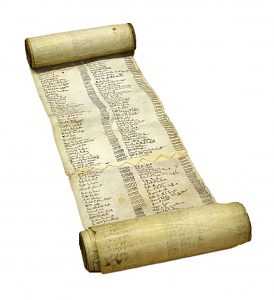

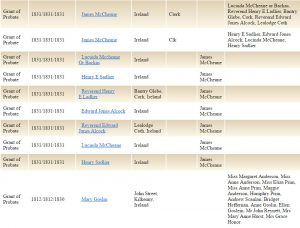

In the course of preparing material for my City Colleges course (new one starts after Christmas, roll up, roll up) I discovered that the brand-new National Archives sub-site, Will Registers 1858-1900, doesn’t include all the surviving material from the post-1857 will registration system.

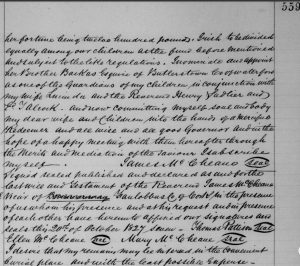

The site states: “copies of wills proved in District Registries from 1858 on survive in Will Registers, and are an exact replacement for the originals which were lost, except of course for the original signatures of the testator and witnesses. Unfortunately, no such copies survive for the Principal Registry, which means there is very little for people who died in Dublin or had particularly large estates.”

This is true in the literal sense that there are no copies. But parts of the originals do survive, at least eleven volumes, and they’re not here.

[Update: a number of people have pointed out that there are in fact Principal Registry Will Books transcribed, though the blurb says otherwise. And the free search interface at FindMyPast allows much more flexible and accurate queries. Maybe there should be a Stage 6: Shame-faced apology? Though I still haven’t found Principal Registry Wills, 1891, G-M.]

And the site has no browse section, and no guide to the years and records are covered – what exactly are the 70,000-odd “Grants of Probate” included? – and, God help us, not even a simple Forward/Back button to page through them.

Still, the fact is that NAI has done a huge service to the research community with the site. It would take so little for it to be complete.

Then I could start again at Stage 1.