We Irish tend to feel, with some justification, that we’re more informed about the past than most other races. Many very old issues are unresolved here. We still have a lot of unfinished history. Knowing that history, and having opinions about it, is part of every Irish person’s base culture.

But there is one area of the past for which we have a deep, wilful blind spot. We suffer from rain amnesia, in particular the virulent sub-variant, post-traumatic summer rain amnesia. On principle, we refuse to recognise that it rains here between May and September. Apart from the occasional hillwalker, no one in Ireland owns rain gear, and very few have waterproof clothing of any description. In a warm pub on a rainy July day, the smell of wet wool can be overpowering.

We loathe wet summers. We take them as a personal insult, and are deeply, bitterly disappointed when it rains in August, even though it always rains in August. So we repress the memories of a lifetime of rainy summers and, come May, expect glorious baking sunshine.

Autumn, when rain is grudgingly accepted, is almost a relief. But not quite. The most common weather conversation remains:

“Grand day”.

“Ah sure as long as it’s not raining.”

As a result, weather forecasting here has to be part psychotherapy. The profession has developed its own jargon, full of defensive euphemisms: “fresh and blustery”, “organised bands of showers”, “scattered outbreaks of drizzle” and, particularly common, “unsettled”. Unsettled means frequent rain. Irish weather is “unsettled” like the Black Death was an outbreak of acne.

Comparing Irish and English forecasts shows just how touchy we are about this. On the BBC, the forecaster will tell you how much, where and when it’s going to rain, perhaps with a rueful shake of the head. On RTÉ, it can never be told straight. A glimmer of desperate hope – “It might be dry in Munster on Thursday!” – is essential before the sheepish revelation of an approaching deluge.

Maybe some things are better repressed. If we remembered accurately, we’d realise that Irish rainfall is always above average.

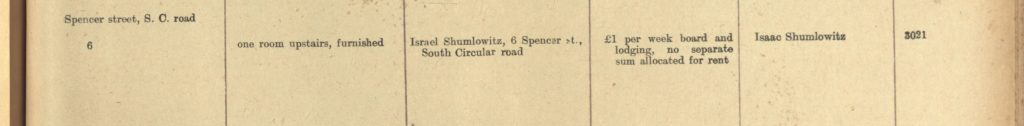

We might be starting to face up to our problem. The Irish Met Office is starting to recover past weather, digitising reports made daily since 1840 in the Phoenix Park (though the results are not yet public). They also have an excellent guide to the locations of historic Irish weather archives and a very interesting day-by-day reconstruction of the weather of the week of the Easter Rising in 1916.

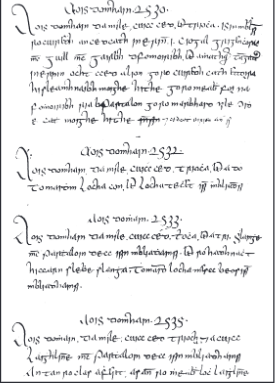

Professor John Sweeney of Maynooth has also done an excellent summary of our historic obsession, including a description of the earliest reference to a meteorological event in Europe, a description in the Annals of the Four Masters to Lough Conn ‘erupting’, allegedly in 2668 BC. We’ve been at it a long time.