Many veteran researchers have a soft spot for the Registry of Deeds in Dublin. Research here is research as it should be, with much climbing up and down ladders hefting giant hand-written tomes, much poring over 200-year-old legal abbreviations and inhaling 200-year old dust. All that’s missing are the powdered wigs.

But an irksome aspect of recent research there has been the Registry’s official policy on photography. It is utterly bananas.

Every archive balances the contradiction between making records accessible to the public in the present and keeping them safe for the future. And every archive except the Registry has long recognized that encouraging readers to take digital images is a near-perfect answer: it decreases wear and tear on the originals and gives readers a chance to chew over complex records at their leisure. But the Registry bans cameras completely and polices the ban with CC-TV in every research room.

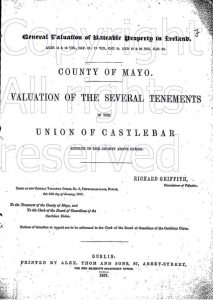

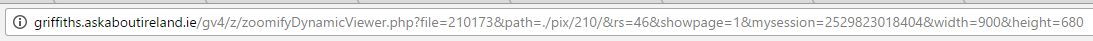

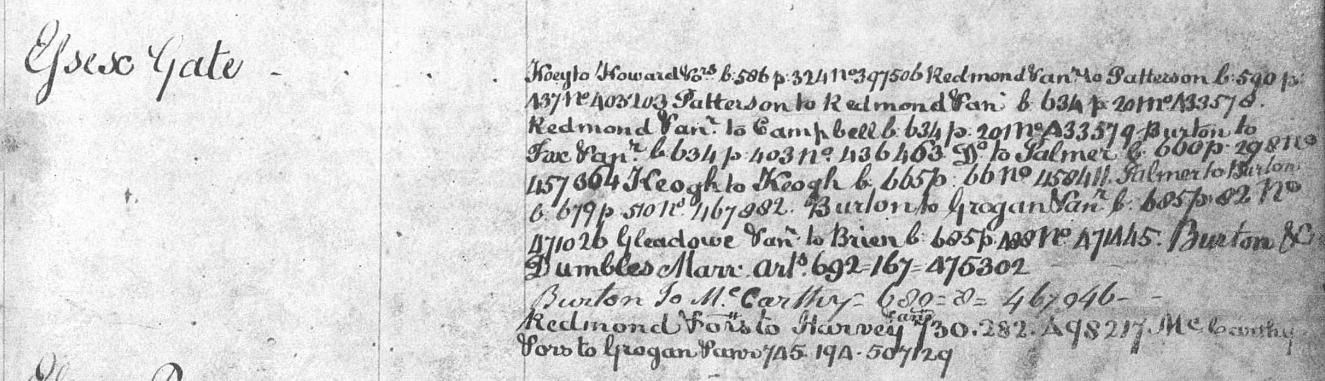

Now FamilySearch.org has rendered the ban moot. So moot, in fact, it couldn’t possibly be mooter. In 1950, the Mormons made a microfilm copy of all of the Registry’s records, Lands Indexes, Grantors’ Indexes, Memorial Books, the lot, all the way from its opening in 1708 to 1929, comprising a massive 2686 microfilms. And they are now digitising the microfilm and making it freely available online. So far, all the Grantors’ and Lands Indexes up to 1929 are complete, all of the eighteenth-century memorial books are complete and about 90% of 1800-1850 memorials are there. The intention appears to be to complete the set.

Hurrah. Almost everything of interest to genealogy is now online, and imaged very well indeed. So much for the camera ban.

Don’t get me wrong. Research on these records remains as cumbersome as it ever was: identify deeds of interest from the indexes; find the matching volume number, then the right page number, then the right memorial. But now, instead of humping 50-pound books up and down ladders, you’re downloading 500 MB microfilm files.

A couple of spin-off implications come to mind. First the heroic volunteer transcription site “Registry of Deeds Index Project Ireland” has depended up to now on its transcribers having physical access to the Mormon microfilms. With direct online access, it should gain hordes of new transcribers and gather serious speed. Hurrah again.

Second, I don’t think I’ll ever breathe that centuries-old dust again. Or maybe ever get out of my dressing-gown.