No matter where in the world your ancestors came from, genealogy eventually shades off into local history. Because of the destruction of so many records in 1922, in Ireland we reach that point much sooner than most other places. I recently reached it myself.

The problem was to interpret records from an early baptismal register from Killian parish in east Galway. Over the first three decades of the 19th century, dozens of families of the same name were recording baptisms, using and reusing a tiny number of forenames. To cap it all, many of the placenames were not listed in any reference sources.

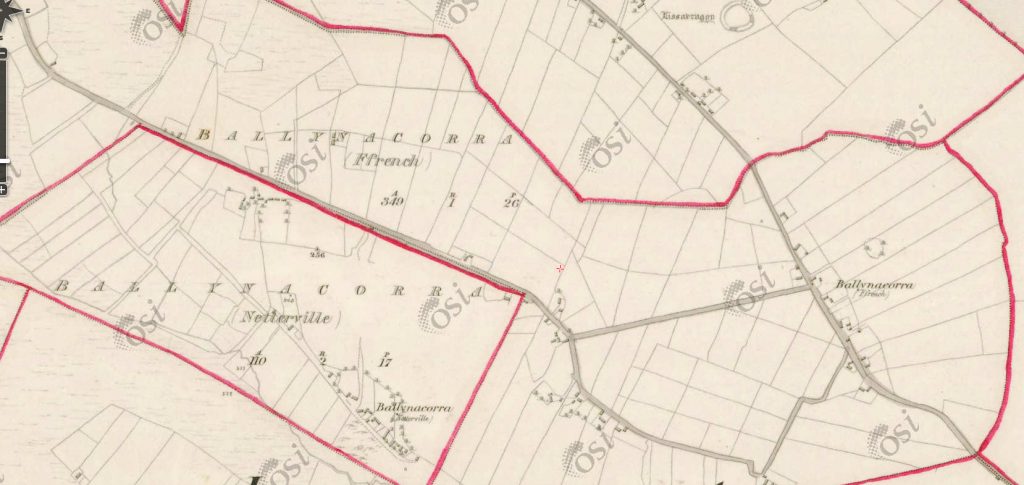

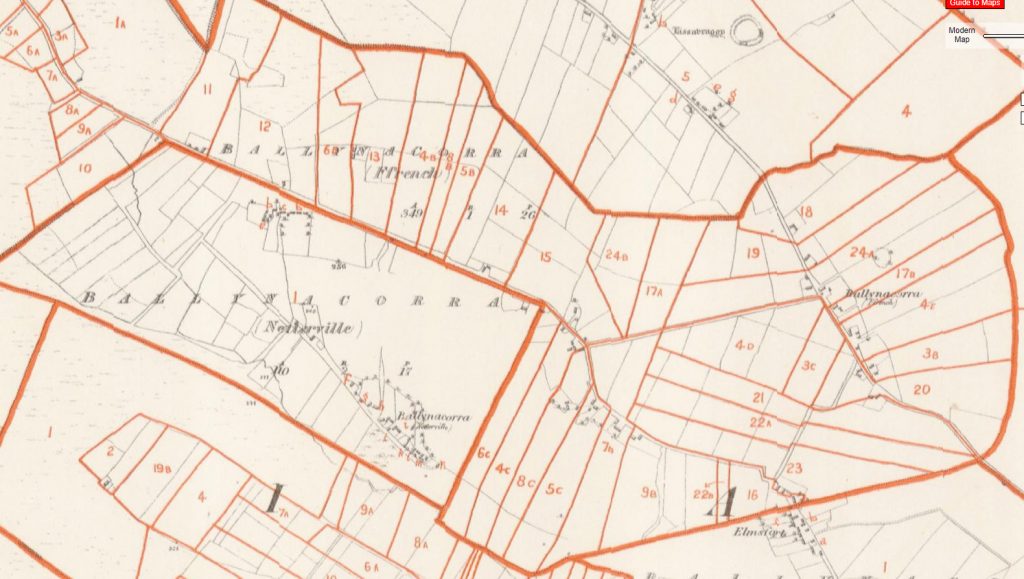

On examining property records and maps, it emerged that there were actually multiple small rundale villages spread over three townlands. Rundale was a tradition of land sharing very close to medieval European practices, which lasted in Ireland up to the mid 19th century and beyond. Small strips of land were co-operatively managed by extended groups of up to 20 or so households, and periodically redistributed. It was deeply uneconomic and loathed by landlords, but the people involved led an intensely rich communal life, with a wealth of traditions, musical, verbal, folkloric, culinary.

Looking at the 1830s map of these mini-villages, some things became clearer. At last I understood the extended family’s weird long-standing attachment to an apparently nondescript patch of East Galway.

It also became clear that I was never going to be able to sort out one family from another with baptismal records, or indeed ever. My idea of what makes up a family just didn’t apply. Looking at the villages on the map, with their tight nets of in-facing houses, vegetable gardens and outlying fields, I could see these people working, dancing, telling stories, intermarrying generation after generation, with intermingling lives that did not have the boundaries that I take for granted.

I’m pretty sure I’ll never uncover the names of the direct generations before 1800. But there’s plenty of compensation in the vivid sense how they lived.