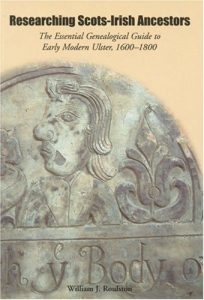

Seven years ago, when the fourth edition of Tracing Your Irish Ancestors came out, Claire Santry didn’t review it, she weighed it. I loved the gesture and I’ve always wanted to find a book for which I could do the same. Step forward William Roulston’s Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors (2nd edition 2018).

The first edition (a svelte ¾ lb, born in 2005) has long been essential for anyone trying to crack those toughest of Irish genealogical nuts, pre-1800 Ulster Presbyterians. They flooded across the Atlantic throughout the eighteenth century and peopled Pennsylvania and Appalachia with astonishing fecundity. As a result, many, many Americans have Scots-Irish in their tree.

The first edition (a svelte ¾ lb, born in 2005) has long been essential for anyone trying to crack those toughest of Irish genealogical nuts, pre-1800 Ulster Presbyterians. They flooded across the Atlantic throughout the eighteenth century and peopled Pennsylvania and Appalachia with astonishing fecundity. As a result, many, many Americans have Scots-Irish in their tree.

Before William’s first edition, when asked to research them, I would tend to stare at my shoes and mumble something about lack of records. With his book to hand, at least I could be clear about what I didn’t know. And now the second edition makes my ignorance pinpoint accurate, weighing in at a strapping 2 lb.

The format is very similar, with chapters on each topic carefully subdivided into numbered subsections, making navigation as easy and intuitive as possible. The familiar categories in the first edition – Church records, Gravestones, Seventeenth Century, Eighteenth Century, Estates, Deeds , Wills, Elections, Military and Newspapers – are all retained and expanded to include material uncovered or accessioned since 2005. In addition, five new sections are added; Migration records; Education, Charity and Hospital Records; Business and Occupational records; Organisations and Societies; Diaries and Memoirs.

The format is very similar, with chapters on each topic carefully subdivided into numbered subsections, making navigation as easy and intuitive as possible. The familiar categories in the first edition – Church records, Gravestones, Seventeenth Century, Eighteenth Century, Estates, Deeds , Wills, Elections, Military and Newspapers – are all retained and expanded to include material uncovered or accessioned since 2005. In addition, five new sections are added; Migration records; Education, Charity and Hospital Records; Business and Occupational records; Organisations and Societies; Diaries and Memoirs.

As in the first edition, the appendices make up more than half the book, almost 350 pages out of a total of 600. And, as before, they are what make the book absolutely essential: the hundred-page county-by-county listing of Ulster estates and their records is worth the price of the book on its own. This is not a how-to, it’s an extraordinary encyclopaedia of historical Ulster, and a wonderful achievement.

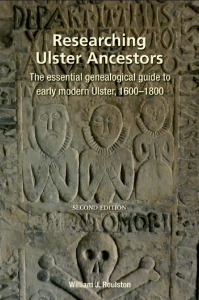

There are a few tiny bones to pick. First, I’d love to see William’s take on nineteenth-century records. The cut-off at 1800 seems a bit limiting.  Second, the book, very strangely, has two titles, called Researching Ulster Ancestors in the UK and Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors elsewhere. Why? Though Ulster Scots are inevitable the prime focus, the records covered are blind to tribal affiliation.

Second, the book, very strangely, has two titles, called Researching Ulster Ancestors in the UK and Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors elsewhere. Why? Though Ulster Scots are inevitable the prime focus, the records covered are blind to tribal affiliation.

And third, the book was published just after my own fifth edition went to the publisher, so I couldn’t plunder all the new material. Curses, foiled again.