I was once told by an American psychotherapist that the Irish have serious problems with bereavement. Apparently we find it very hard to let go. Maybe that’s the reason we have such a thing about graveyards. Because we certainly do have a thing about graveyards.

Last week I checked the site historicgraves.com and discovered the number of places covered had more than quadrupled in three years. It took two whole days just to add them into the listings (check out Limerick just to get a sense of the scale).

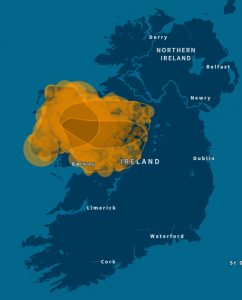

Historicgraves depends on volunteer community projects and often records much more than the inscriptions, going into the detail of the heritage of each graveyard. It currently has transcripts for 484 cemeteries, mostly in Cork, Limerick and Tipperary, though there are also significant numbers elsewhere.

There are also two other Irish groups wholly dedicated to transcription and free publication of inscriptions, www.discovereverafter.com and www.irishgraveyards.ie. Both are private companies supplying cemetery management services, with online transcript collections as a kind of by-product. Discovereverafter is based in Derry, with most of its transcripts from counties Derry, Tyrone and Armagh (118 graveyards currently). Irishgraveyards is based in Castlebar, and covers mainly Mayo, Galway and Donegal (74 graveyards).

All three adhere to the current gold standard: transcript, headstone photo and map. Despite their current regional focus, all three also appear to have country-wide ambitions.

This is not to mention the transcriptions being carried out by heritage groups supported by local authorities or libraries: in Galway, West Cork, Kildare and Meath, Clare, Wexford … Where have I missed?

And then there’s the IGP archives, volunteer-supported and growing rapidly – their transcripts for Mount Jerome in Dublin (to mention just one) are superb. Not to forget Dr. Jane Lyons’ massive collection of more than 70,000 records on her site from-ireland.net .

Many non-Irish sites have also picked up the bug. There are plenty of Irish transcripts on the venerable interment.net and findagrave.com, and many Irish headstone photos on gravestonephotos.com.

The work of previous generations of transcribers hasn’t gone away either. For Northern Ireland by the Ulster Historical Foundation has a huge transcript-only collection for Ulster at ancestryireland.com. Other IFHF members are putting their collections on rootsireland.ie, with Derry, East Galway, South Mayo, North Tipperary and Westmeath leading the pack.

And of course more than a century’s-worth of published transcripts are also out there.

- The Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead ran from 1888 to 1934, recording tens of thousands of inscriptions, many now gone – the journals up to 1909 are now online at archive.org.

- Brian Cantwell’s life’s work, Memorials of the Dead, comprising c. 24,500 inscriptions, covering all of Wicklow, Wexford and part of Dublin, is widely available in major libraries and is online at FindMyPast. Seaboard Mayo and Galway sites were transcribed by his son Ian, whose site www.iancantwell.com includes indexes, as well as an interesting history of memorial transcripton and methodological analysis.

- Albert Casey’s gargantuan 17-volume O’Kief, Cosh Mang, Slieve Lougher, and Upper Blackwater in Ireland covers 42 graveyards in Cork and 36 in Kerry.

I could go on …

One of the strange upshots is that more and more cemeteries have multiple transcripts. Current leaders (as far as I know) St. James’ (Mervue) in Galway and Agher in Meath, each transcribed no fewer than four separate times.

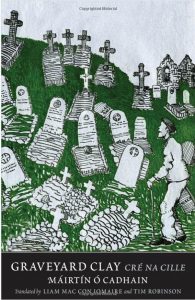

Mairtín Ó Cadhain’s Irish-language masterpiece Cré na Cille takes place in a graveyard, with the dead giving out to each other, making scurrilous jokes and complaining about the living. I suspect a sequel might have them pleading with transcribers to leave them alone for a while.

Mairtín Ó Cadhain’s Irish-language masterpiece Cré na Cille takes place in a graveyard, with the dead giving out to each other, making scurrilous jokes and complaining about the living. I suspect a sequel might have them pleading with transcribers to leave them alone for a while.