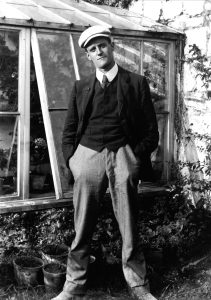

With genealogy blinkers on and up to your tonsils in luverly, luverly databases it can be hard to grasp the implications the records have for other areas of research. An obvious beneficiary is Joycean studies. Many of James Joyce’s characters are based on real individuals, often appearing under their own names. The period he writes about is slap in the middle of the 1901 and 1911 censuses, transparent and free online; Dublin parish registers are also online; and Dublin newspapers, and Dublin directories, and Dublin voters’ lists and maps and …

A few examples: Miss Douce “of the bronze hair”, immortalised in the Sirens episode of Ulysses, set in the Ormond Hotel, was actually Maggie Dowse, “manageress” of the Bailey in Duke St. in 1901 and a sister-in-law of the owner, William Hogan. No doubt “Douce” was a more suggestive variant.

The Dubedat family are celebrated in one of Ulysses’ many joyously puerile jokes – “May I tempt you … Miss Dubedat? Yes, do bedad. And she did, bedad.” And there they are in Dublin Church of Ireland registers, the Du Bedats, Du Bidats, Dubédats …

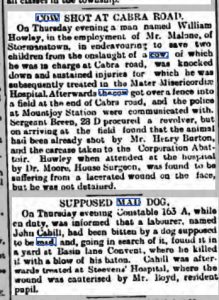

Like genealogy, collecting Joyce trivia can become compulsive, and can lead in unexpected directions. A four-word headline noted in passing in Stephen Hero, “Mad Cow at Cabra”, recalls the practice of driving cattle through the city streets from the markets in Prussia Street via Phibsborough down to the cattle boats at the North Wall. Sometimes, understandably, a cow would run amok. As so often in Joyce, even the tiniest details are made out of real incidents. The Irish Times of April 2 1904 has two tiny news-items side by side on page 6: “Cow Shot at Cabra Road” and “Supposed Mad Dog”. Maybe even Joyce sometimes got confused?

For more Joycean fun see jjon.org.