One of my record-keeper heroes has long been Sir William Betham (1779 -1853). He arrived in Dublin for a brief visit in 1805 and by chance found himself wading through the chaotic collections of records held in Dublin Castle. As a result, he went about acquiring authority over the Bermingham Tower records, by getting an appointment as Deputy Ulster King of Arms.

Ulster’s Office was the heraldic authority for the island of Ireland, responsible for providing confirmation of their social status to the Anglo-Irish elite: the right to bear arms was (and is) purely hereditary and thus an indicator of supposed good breeding. So as well as putting order on the Office’s existing records, Betham set about creating a new reference collection covering the propertied Anglo-Irish, the Office’s clientele.

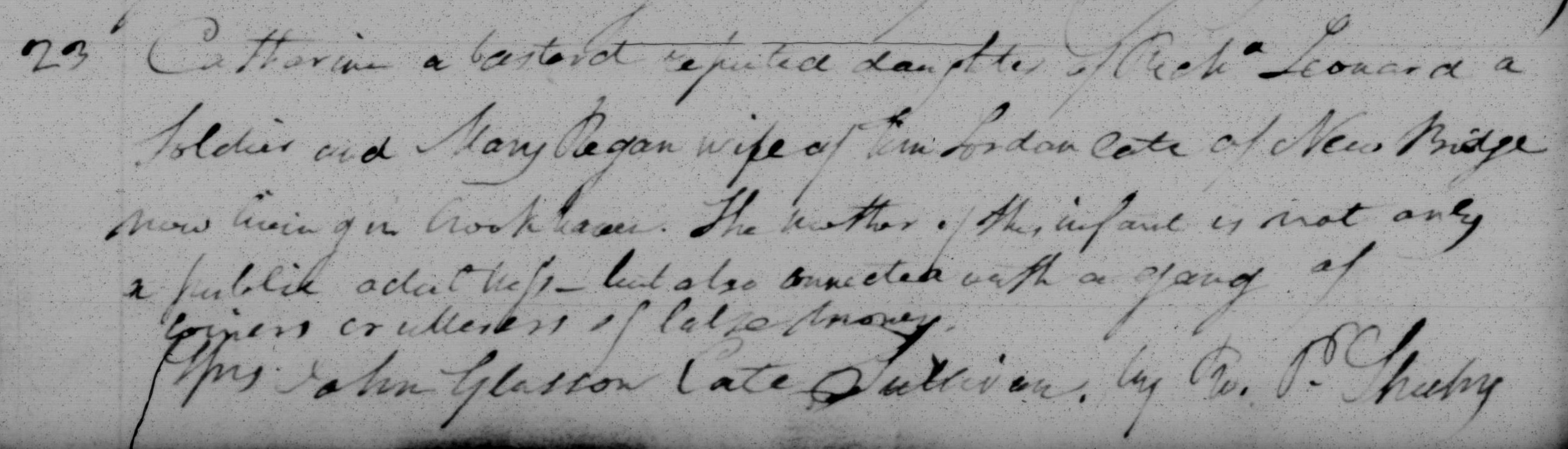

By far the richest source of family information on the propertied Anglo-Irish was the collection of prerogative wills held at the Prerogative Office in Henrietta Street. A prerogative will was one with property worth more than £5 in two probate districts ( Church of Ireland dioceses), meaning they tended to cover the top end of the social scale, the Office’s main market.

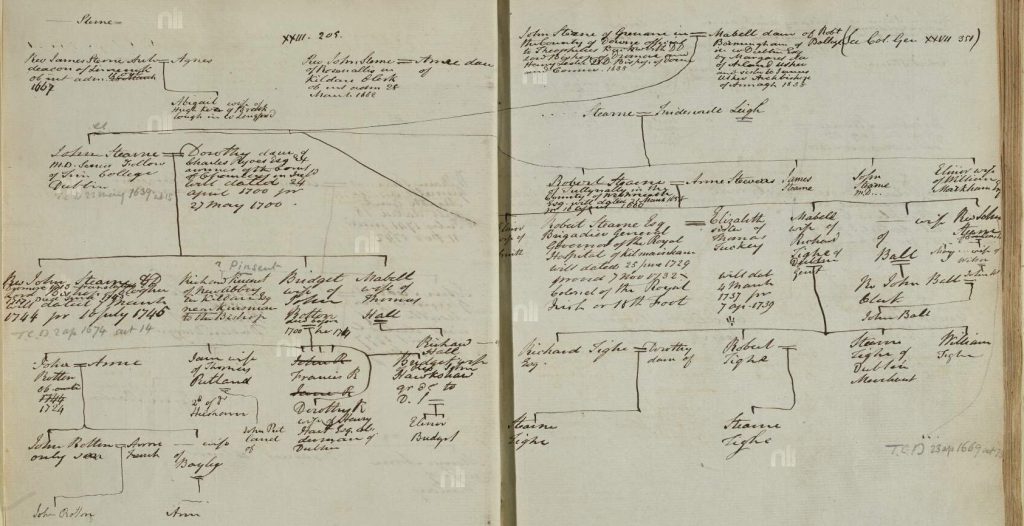

In 1807, Betham began to transcribe all the family information recorded in these wills, coming from 1536 right up to 1800. The project took him a full twenty-one years to complete, by which time he had become Ulster King of Arms himself. With the information from the wills, he then created a series of volumes of sketch pedigrees that provided ready-made pigeon-holes for any subsequent information that turned up. These volumes, more than forty in all, are in the Genealogical Office, the successor to Ulster’s Office, now part of the National Library of Ireland and are being digitised superbly through NLI’s online catalogue.

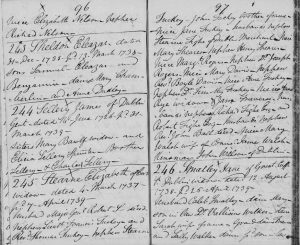

The original notebooks Betham used for the transcriptions were purchased by the National Archives of Ireland in the 1930s and microfilmed by the LDS in 1969. And as part of their program of enhancing online access, those microfilms are now freely available online to signed-in users.

The transcripts are a magnificent source for eighteenth-century Irish ancestors, not only because we blew up all the originals in 1922, but also because the social range covered by the wills is much broader than Betham’s original intentions implied. Shoemakers, ironmongers and small tradesmen of every description are also included. If you lived near a diocesan boundary, it was very easy to have £5-worth of property in more than one diocese.

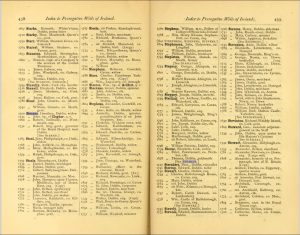

On the back of the LDS release, FindMyPast have come up with a transcript which I have to say I find a little puzzling. It gives no indication of where the originals are, that the images come from LDS microfilm or that the notebooks are part of a wider set of records. And then lumps the will transcripts in with Marriage Licence Bonds extracts.

But (with a bit of ingenuity) it is possible to use the index to zero in on particular entries in the notebooks, cutting out some of the to-and-froing necessary on FamilySearch. Small mercies.