You may have noticed the absence of a post last week. I’d like to be able to say that I was deep in my vast library thinking profound thoughts about the future of Irish genealogy. But no, the sun came out so I took the dog to the beach.

I wasn’t completely idle, though. I went on the Guinness.

I wasn’t completely idle, though. I went on the Guinness.

At a professional development presentation organised by my accrediting association, Accredited Genealogists Ireland, and delivered by Guinness archivists Alex Marcus and Fergus Brady. It was a revelation.

Like most researchers, I’ve long been aware of the archive’s online catalogue (also available on Ancestry) and have found it interesting but a bit scanty. With 8,697 entries, it is obviously not a listing of all employees, and each result leads only to a very bare-bones record.

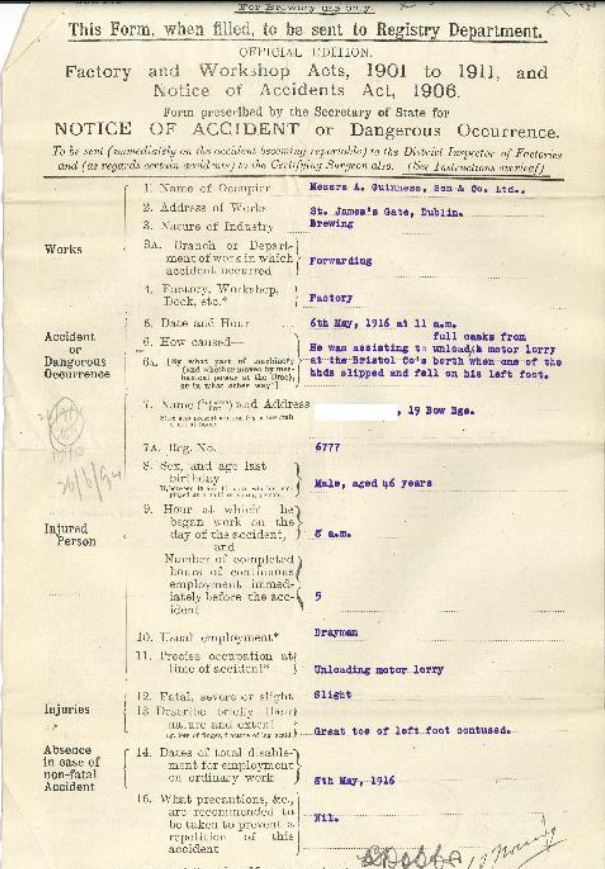

The archive itself is something else entirely. It holds more than 20,000 personnel files relating to deceased employees. For the majority of these, tradesmen or labourers, the files can include dates of birth, addresses, references, education, accident reports, changes of job, pension forms, medical information, physical descriptions, widows and orphans allowances, details of wives and children, even birth and baptism certificates. For the expanded family history of anyone who worked in Guinness’s in Dublin after the 1870s, these records are a goldmine.

One of the most interesting parts of the presentation was the explanation of the reasons behind the lack of online detail. Guinness was a spectacularly benevolent cradle-to-grave employer. Once a family got a foothold, they tended to bring in other members, with children, grandchildren, great-grand nephews following each other into the firm (see the remarkably guff-free Cillian-Murphy-narrated ad on this). So even the files of those who died a century ago might hold sensitive information relating to living people.

But there are no Germanic GDPR-style prohibitions. The archivists just check the files you’re interested in and apply good old-fashioned common sense. They’ll do this by email, but there’s no substitute for handling the files onsite yourself, and they welcome visitors (by appointment).

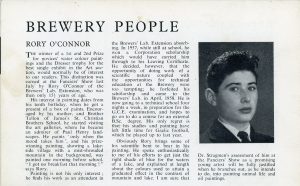

Apart from the files, the archive also holds a spectacular digitised set of the in-house publications, in particular The Guinness Harp Magazine, which documents the extraordinary range of extracurricular activities sponsored by the company, from choirs to chess clubs to tug-of-war teams, complete with professional-quality journalism and photography.

And there’s also a lovely collection of the customisable labels used to reassure drinkers that the pub-bottled stout they were drinking was genuine Guinness.

My lifetime supply can be parked just outside the house, please.