One of the joys of genealogy is coming eyeball to eyeball with the past in all its weird particularity. It produces two apparently contradictory effects. On the one hand, you get to appreciate that a century ago (or twenty centuries ago) human beings everywhere were just as human as we are, with all the fears and desires that we have. On the other, you realise how alien and remote the past can be. It is just not possible to recapture what it felt like to live inside the elaborate warrior-dominated caste system of pre-medieval Ireland or to be forced out of a WW1 trench knowing you face instant, certain death.

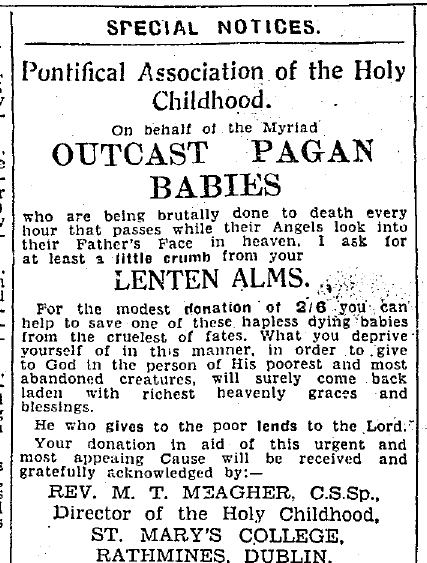

Alien and remote: Irish Independent Apr 1, 1939

So when I saw the tag-line for the GPO 1916 museum in Dublin – “So real you almost smell the gunsmoke” – my hackles rose. What about the smell of gangrene? Or the dead horses rotting out on Sackville Street? The museum (full title “The GPO Witness History Museum & Visitor Centre“) has won international awards, provides a nice day out and does what it does very well indeed. But what it does is provide immersion in a sanitised past, a theme park version of history carefully relieved of anything truly strange or upsetting.

This obligation to immerse seems to be part of a bigger trend in the leisure sector, of which history and genealogy are now minor branches. So 3D cinema is no longer enough, we’re now on to 4D. Which apparently involves splashing water on everyone when a boat appears, puffing out scent to accompany flowers and (one can only hope) eventually disembowelling an audience member live during ‘Halloween 39: Great-Grandson of Freddie’.