My contract with the National Archives to clear the backlog of census corrections emails has come to an end. After eighteen months of grinding through 250 emails a day, it’s a bit of a relief. Yes, I managed to suck the 102,000 outstanding emails into a database that allowed easy comparison between the original image and the suggested corrections, and yes that also meant it was possible to identify many duplicate suggestions.

But the low-hanging fruit were all picked a long time ago. Over the past months most of the corrections seem to be along the lines of “My granny was 17, not 16. And her surname was Browne, not Brown.”

Argh.

The 90,000 emails (88% of the total) contained almost a quarter of a million suggestions, 95,000 correct, 80,000 duplicate and 40,000 inaccurate. I can guarantee there will be no official enquiry into cost overruns or ballooning budgets.

Exposure to the censuses at this scale gives insights into some of their peculiarities. A surprising number of people in 1901 and 1911 were hazy about precise family relationships. Grandparents repeatedly list their grandchildren as nephews or nieces. Why? In Italian nipote actually means both “grandchild” and “niece or nephew”, so perhaps something deep in our mental family structure equates the two-step distance of sibling’s-child and child’s-child. Or maybe it was just doddery grandparents. In any case, their descendants wanted it corrected. And of course it couldn’t be, because whatever was recorded on the form has to appear in the transcript.

The transcribers enforced this fanatically when it came to religion, for some reason. Not surprisingly, many people wanted “Roaming Chatilic”, “Presbitrian” and “Babtist” corrected, but if that’s what was written … On the other hand, there were many stinkers in Ireland a century ago, but none recorded “Free Stinker” as their religion.

The most poignant were emails where people expanded on the information supplied, correcting “Scholar” to “My grandmother”, expanding initials or later lives or even, in one case, washing the family dirty linen a century later:

Transcribed: John Murphy son 10

Correction: ILLIGITIMATE NO RELATION

The mistranscriptions kept me sane, especially the occupations: “Panty boy” for Pantry boy, “Alien apprentice” for Draper’s apprentice, “Publican and Flasher” for Publican and Flesher, and the evergreen “Penis tuner” for “Piano tuner”. Fine old Edwardian trade, penis tuning.

I also came across unexpected individuals. The real Thady Quill, not rambling, nor roving, nor footballing, nor courting, just a simple farm labourer.

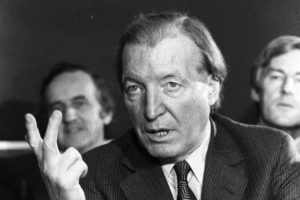

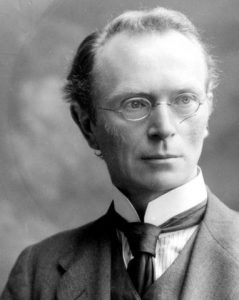

Alas Eoin McNeill no longer leads the Garlic League .

But the League lives on!