Irish research doesn’t have many under-explored collections, so you’d expect joy unconfined to surround the records of the Valuation Office. However, most researchers’ eyes glaze over when you mention them. And for good reason. The Office is one of the oldest continuously functioning arms of public administration in Ireland, set up in 1826 and still operating today. That’s almost two centuries, long enough to produce entire Himalayas of paper, which include some of the gnarliest records imaginable.

The Office’s basic role was (and is) simple enough: to create property valuations on which local property taxes could be based. Its main achievement was Griffith’s Primary Valuation of 1847-1864. But the creation of Griffith’s was far from simple.

The initial Townland Valuation Act (1826) allowed for a complete assessment of the annual value of every parcel of land and building in Ireland, with the aim of producing a total for each townland that could be used as the basis of a yearly tax. But in 1826 nobody even knew what townlands were where, so the project became dependant on, and intertwined with, the Boundary Commission and the Ordnance Survey.

The earliest OS maps were produced for Londonderry in 1831 and it was then and there that surveying began. Richard Griffith, the Valuation Commissioner, quickly saw that the plan to value everything was far too ambitious for the resources available. While continuing to value all land, a threshold of £3 annual value was adopted for buildings to be assessed, excluding the large majority of householders but still covering a significant number of dwellings and commercial premises, especially in towns. The valuation continued on this basis for the next seven years, covering eight of the northern counties. By 1836, however, it was clear that even with a £3 threshold the surveying would never be completed. In that year the threshold was raised to £5, covering only the most substantial buildings.

The year 1838 saw the introduction of the Irish Poor Law, a rudimentary system of relief for the most destitute, and its funding was based on a separate property survey. It quickly became obvious that it made no sense to have two separate systems of local taxation, based on differing valuations of the same property. In 1844, with townland valuations complete for 27 of the 32 counties, Griffith was authorised to change the basis of assessment by dropping the £5 threshold and covering all property in the remaining counties, all of them in Munster.

The Tenement Valuation Act (1852) retrospectively allowed Griffith to extend the system throughout Ireland – a procedure he had in fact already begun. Over two decades of valuation he had assembled a veritable army of skilled employees, each with a precise role in his vast valuing mechanism. It allowed him to publish county-by-county surveys of the entire island between 1847 and 1864, generally with the southern counties earlier and the northern counties later.

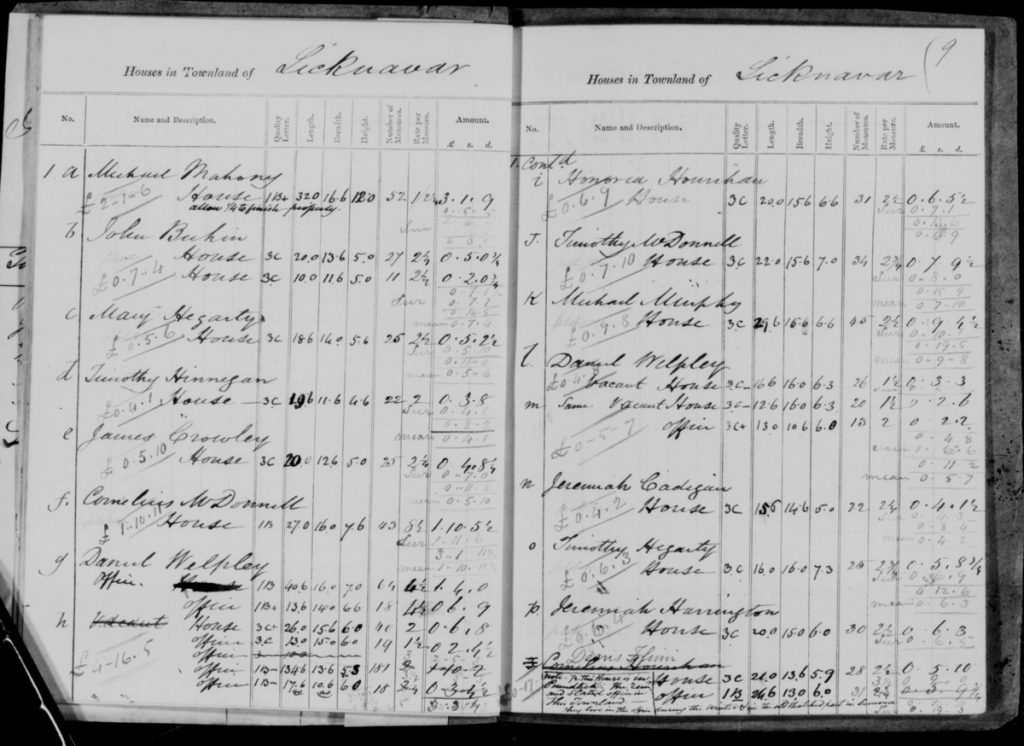

In the course of this long-drawn-out saga, huge quantities of manuscript records were produced. Firstly, the pre-1836 valuation of the northern counties, based on the £3 building threshold, created local valuers’ “house books” and “field books”, the former including the names of occupiers, the latter in theory at least concerned purely with soil productivity. They remain particularly useful for urban or semi-urban areas in northern counties before 1838.

After the change in the basis of assessment in 1844, the main categories of valuers’ notebooks continued to be known as ‘house books’ and ‘field books’, but the distinction became more than a little blurred, with information on occupiers appearing in both. To add to the merriment, other classes of notebook were also created:

- Tenure books, showing landlord and lease information;

- Rent books, showing rents paid, as an aid to valuation;

- Quarto books, covering towns,

- Perambulation books, recording valuers’ visits, and

- Mill books.

There are far fewer of these than of the ‘house’ and ‘field’ books.

The survival of pre-publication Valuation Office records is patchy, with some parishes having four or more books while others have none at all. The only way to find out what’s there is to examine the records themselves. There are two major collections, one in PRONI, the other in NAI. The PRONI records cover only the six countues of Northern Ireland and are only available onsite in Belfast. It’s not clear from the information they provide that any of the post-1844 books are publicly available. In 2003, the LDS microfilmed the entire collection then held by NAI and this is the collection now online at genealogy.nationalarchives.ie.

Another set of records, held by the Valuation Office itself until 2003 and subsequently moved to NAI, is still being catalogued and conserved and so is not as yet publicly available. The word is that it includes thousands upon thousands of valuers’ hand-made maps, with the tantalizing prospect of detailed field and townland maps that will hold a magnifying glass to rural Ireland of the 1830s and 1840s.

NAI has done a wonderful job of making the earlier microfilmed records intelligible and accessible. Written by former director Frances Magee, the introductory text for each of the manuscript types is a master-class in the valuation process and the codes used by the valuers. She has a book on the Valuation Office collection in the works, due out some time in the next twelve months. Roll on the day.

One caveat about the database transcripts. Something funny seems to be happening on the NAI site. Compare the search results for a Martin Heavy on FindMyPast with the results on the NAI site. There should be no difference – they’re the same underlying datasets. For the moment, the FindMyPast search is the one I trust. It’s free and also permits browsing by parish, something not available on the NAI site.

These records might seem marginal and messy compared with the published Valuation, but keep in mind that Griffith’s, far from being the record of a settled population, is a snapshot of the aftermath of a catastrophe, the Great Famine. In many areas enormous changes took place between the original survey and final publication. In the area around Skibbereen, for example. the pre-publication records are be the only surviving evidence of entire villages that were wiped out.