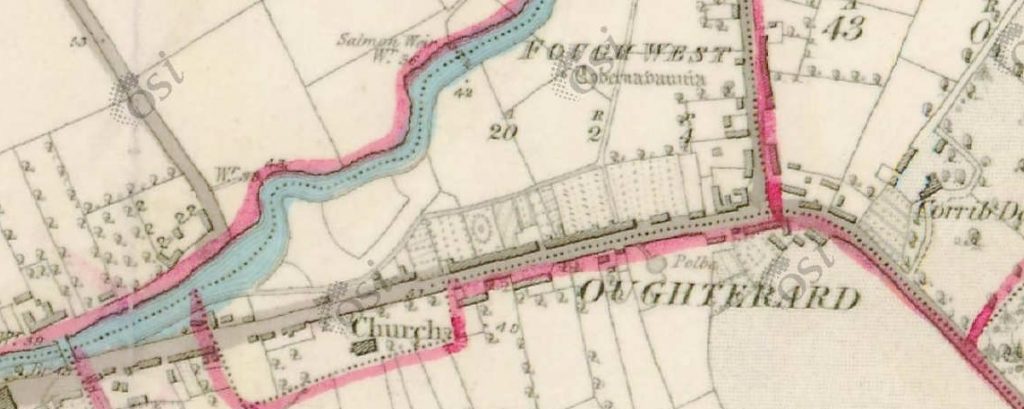

As anyone who has used my website knows, a lot of it depends on maps that visualise the historic locations of households and records in particular areas of Ireland. Users can then (mostly) click through to the actual records.

The original inspiration came from a book by Edward Kneafsey, Surnames of Ireland (2002, the author), which took the 200 most numerous surnames on the island and created an individual ‘dot-density’ maps for each, based on a count of surnames by phone-code areas.

The results were striking, with clear visual connections between population density and traditional home areas. So I said to myself “Wouldn’t it be interesting to do the same online for the 20,000 or so surnames recorded between 1847 and 1864 in Griffith’s?”

It took months of weeping, wailing, teeth-gnashing and keyboard-headbutting to figure it out, but eventually I managed to use Google’s Geocharting javascript to do it. I was as pleased as punch when it all went live on the old Irish Times ‘Irish Ancestors’ site in 2012. It’s still at the heart of the main surname search page on this site.

There are limits to how interactive geocharting can be – it’s not possible to create links in the markers, for example – so I then started to investigate the main Google Maps javascript, where there is much more flexibility. Cue another two years of weeping, waling, gnashing … In 2015, I worked out how to map the birth indexes then appearing on IrishGenealogy.ie onto Google Maps locations of registration districts and include on the map marker a link back to the records on IrishGenealogy. And then came the 1911 census. And the 1901. And the FindMyPast Catholic baptism transcripts …

All of this depended entirely on the enlightened self-interest of Google’s pricing of access to their maps. There was a generous free allowance of 750,000 monthly map hits, way beyond what I would ever need. Even above that limit, the prices were painless.

Then last July, with a month’s notice, the monthly allowance shrank to 28,000, a drop of 96%. And the price for usage above the limit increased by more than 1,400%. Some MBA in Palo Alto, red in tooth and claw, had evidently decided there were enough fish in the barrel and it was time to start shooting. The usual Google trade-off of information to sell advertsing in return for a free service was no longer enough. This is the baseball bat business model: “Nice maps you got here. Shame if anything happened them. Capeesh?”

This is the baseball bat business model: “Nice maps you got here. Shame if anything happened them. Capeesh?”

Faced with the prospect of having to pay thousands a year for a previously free service, I’ve moved most of the maps to the open-source-based MapBox. There will still be payment, but at least not to Google.

For me this is a nuisance. For developers in parts of the world where Google has a monopoly of map data, it’s a business-destroyer, with a single flat US$ price regardless of circumstances or local going rates.

It has been a revelation. Don’t be evil.