There aren’t many Irish sources that can give you a from-the-horse’s-mouth account of the country between 1830 and 1850. And there really really aren’t many such sources that are poorly known about, underused and free online. Two parts of the Ordnance Survey Ireland archive are just that.

The Ordnance Survey Name Books and the O’Donovan topographical letters are both by-products of the massive attempt between 1828 and 1848 to record and standardise Ireland as a prelude to taxing it. The Name Books are parish-by-parish alphabetical listings of the place-names that were to become the standardised English versions on the first Ordnance Survey six-inch maps in the 1830s. The entries include much technical detail linking them to the maps, but also some worm’s-eye-view descriptions of rents, landlords and tenants, adduced as evidence for the names.

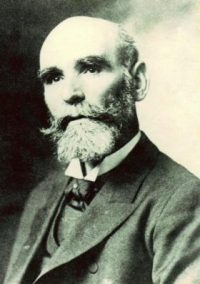

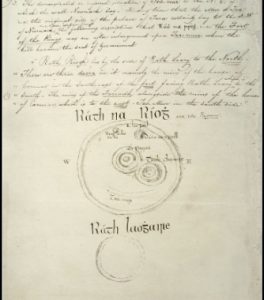

The O’Donovan letters are of broader interest. They consist of formal correspondence to or from the man in charge of the Ordnance Survey topographical department, the antiquarian John O’Donovan, and often provide superb summaries of local place-name lore, even down to the most minute detail: the entry for Darver in Co Louth includes a description and drawing of “a silver ring which Mr Duffy found near his house”. For anyone interested in local history in rural Ireland they are a boundless treasure trove. And they give the lie to the notion that the OS process of standardisation and anglicisation was brutal, Anglo-Saxon and stupid. See the full OSI archive listing at the Royal Irish Academy.

Both Name Books and O’Donovan Letters are available for free on askaboutireland.ie, where the versions used are typescript copies of the originals made in the 1920s. Most users become aware of them as links on the OS maps that accompany Griffith’s search results, and it has to be said that there are serious drawbacks to this approach. But they are also browsable page by page, revealing all their gnarled glory, with folk-tales, principal families, ruined churches, annal entries, saint’s biographies and more. Many county library websites (e.g. Clare, Galway and others) also have copies of the Letter books online.

The voice of O’Donovan himself is also there, and strangely modern. At the conclusion of the second volume of Galway letters, he writes: “I have now done with the territories in the county of Galway and though it has cost me many an hour of severe application to lay down their boundaries I fear no one will have the patience to grope their way through my lucubrations.”

He shouldn’t have worried.