The central event for anyone researching Irish history is the destruction of the Irish Public Record Office in 1922. For the previous century-and-a-half, Ireland had been methodically measured, counted and recorded unlike anywhere else in the then United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, precisely because it was contested territory. We had the first censuses, the earliest systematic maps, the first centralised police force, the first uniform property taxes, the first island-wide legal system.

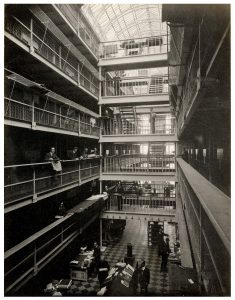

And from 1867 we had a wonderful state-of-the-art Public Record Office to secure the records of all that activity.

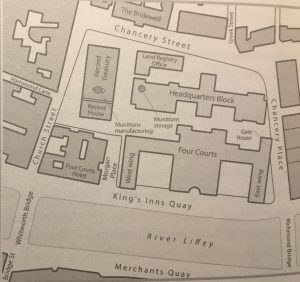

The broad outlines of what happened in 1922 have long been clear. The opponents of the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty occupied the Four Courts campus (which contained the Public Record Office) in April 1922. Their aim was to force the Treaty signatories, their former comrades-in-arms, to choose between upholding the Treaty and starting a civil war or resuming the war against Britain.

On June 28 1922, after an ultimatum was rejected, the pro-Treaty forces began an assault and bombardment of the Four Courts that resulted in the complete destruction of the PRO and all the contents of its Record Treasury three days later, on Friday June 30.

There followed almost a century of tit-for-tattery over who was to blame. Anti-Treaty zealots who mined the entire complex and wanted history to restart from Year Zero? Or incompetent Free-Staters using British Army artillery they couldn’t control? Take your pick: Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael?

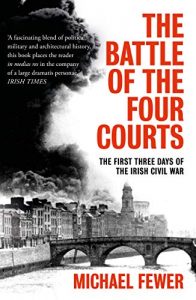

And there was always a convenient haziness around the exact sequence of events over that week in June 1922. No more. Michael Fewer’s The Battle of the Four Courts: the first three days of the Irish Civil War (Head of Zeus, 2019) is a meticulous work of micro-history that assembles the story hour-by-hour weighing maps and photographs against eye-witness accounts to reconstruct an utterly convincing version of what happened.

And there was always a convenient haziness around the exact sequence of events over that week in June 1922. No more. Michael Fewer’s The Battle of the Four Courts: the first three days of the Irish Civil War (Head of Zeus, 2019) is a meticulous work of micro-history that assembles the story hour-by-hour weighing maps and photographs against eye-witness accounts to reconstruct an utterly convincing version of what happened.

As Fewer tells it, there is plenty of blame to go around.  The Anti-Treatyites stored their huge supplies of munitions in a building adjacent to the Record Treasury (the “Headquarters Block”) and booby-trapped it with fire-bombs. The Free-Staters breached the defences of the complex by blowing a large hole in the Church Street side of the PRO Reading Room and attacking through it. The attack triggered the booby-trapped munitions and the resulting explosion was immense.

The Anti-Treatyites stored their huge supplies of munitions in a building adjacent to the Record Treasury (the “Headquarters Block”) and booby-trapped it with fire-bombs. The Free-Staters breached the defences of the complex by blowing a large hole in the Church Street side of the PRO Reading Room and attacking through it. The attack triggered the booby-trapped munitions and the resulting explosion was immense.

The explosion demolished most of the block and started a ferocious fire. It did not destroy the Record Treasury, but blew out all of the vast glass windows and left the records at the mercy of the holocaust. It took hours for them to be consumed, while the Dublin Fire Brigade looked on helplessly, unable to intervene for fear of further explosions. After it had burnt itself out, everything in the Treasury was gone.

The simple fact is that neither side cared a damn about the records. They were young men prepared to kill or die for their beliefs about the future. What did the past matter?

There are some positives from what happened, if you squint really hard. First, 1922 simplified Irish research, though perhaps only in the way that Cromwell simplified Ireland. It is also one of the main reasons so much basic Irish material (the bits that survived) is so widely available for free on Irish government websites such as irishgenealogy.ie, genealogy.nationalarchives.ie and registers.nli.ie. Never underestimate the power of institutional shame.

There are also attempts to put things right. The successor to the PRO, the National Archives, is very gingerly restoring some of the burnt bits in time for the centenary. And Beyond 2022 is aiming to repopulate as many of the empty Treasury record bays as possible. Good luck to them.

This is very fascinating. I was in Ireland last spring and saw these buildings, and wanted to know more about them. Thank you for the story, and book reference.

The buildings are right near the church we were looking for – St. Paul’s.

Thank You for the article, How the Public Office burned

Thanks for the update John.

Yes the past -what does it matter when they were so intent on creating a new future!

I have some good records due to the fact many of RC church records did not get sent to Dublin but what would have the 19th century census shown? alas we will never know ……

I found transcriptions of records from the 1821,1841 and 1851 censuses for a few branches of my family in Kilkenny that have added details that church records and gravestones never could. These were transcribed over many years by Canon William Carrigan along with many other records subsequently destroyed. I hope these will shortly be added to the virtual record office as they are really helpful.

The IFHF centre in Kilkenny has just added the Carrigan transcripts to their online collection – see https://rootsireland.ie/kilkenny/online-sources.php

Ahh, very good! I have been rabbiting on about them for years. A pity he didn’t transcribe more or even better still if the record treasury hadn’t burned in the first place!

Hi John – Since I did the diploma with you in 2017, I’ve found out that Padraig O’Connor (of the Free State side that blew a hole in the building to get in) was my Grandad’s cousin. He left a written account which is fascinating to read.

Thanks John. While the root cause is certainly regrettable, the “institutional shame” has been a boon for researching from way out here in Southern California. Adding to it, there’s also the “unforced errors” of the destruction of the later 19th century censuses, prior to 1922. It only makes the intrepid researcher delve that much harder, pulling extant documented threads together like a mouse-bound forensic historian, and now I have some fascinating family black sheep’s stories revealed in past Irish generations, on my dad’s side, to provide compelling counterpoints to the American ones on my mom’s side.

I’m truly grateful for Ireland’s (and Northern Ireland’s) commitment to sharing these resources online. Really hoping to see the Republic’s Griffith’s Revisions appear on the web at some point.

Parting shot / pro bono copy editing: you introduced Mr. Fewer as Michael “Farmer”.

Brilliant work John! Thank you!

Got a copy of this book for Christmas, have just read the first two chapters and it has me hooked, so interesting. Michael Farmer has certainly done his homework. Good luck indeed to the National Archives on the mammoth task ahead, hopefully their great intentions pay off.

Thank you, Mr. Grenham, for this story on How the Record Office burned. What a calamity for Ireland, in deed!

I have been researching my Irish ancestory for some 10 or more years. Bit by bit, I’ve been able to find a goodly number of ancestors, particularly those on maternal branches that feed into my paternal line.

In the main, I depend on your website and the links to irishgenealogy.ie, Griffith’s Primary Valuation, Tithe Applotment Books, etc. etc. to discover my ancestors. You have inspired me to produce more than just a genealogical family tree. The real interesting stuff lays in determining what my ancestors did for a living, where they lived, who they married, who their children were, who the children married, and so on. Each BMD document has to be analyzed for its content to link people through the generations. Genealogy, it seems, is the art of finding individual pieces of evidence and putting those pieces together, much as one works to complete a puzzle!

Unfortunately, I have just about exhausted all hope of finding any information on my great, great, grandfather. At the time his son James marries a girl in St. Mullins, Co. Carlow, in 1853, he is a shoemaker living in Mullingar. I have no other dates or people associated with this individual.

A Mullingar shoe merchant is listed in Thom’s Irish Almanac of 1877 but not 1862. My grandfather doesn’t own the shop it for his name is not mentioned. But the Devine story that I write for my offspring and their children is that their great, great, great grandfather or their great, great, great, great grandfather (as the case may be) likely shod boots for the British military, as Mullingar back then an, t’il quite recently, was home to a military barrack within the jursdiction of British military forces in Dublin.

I have written the above passage to show just what you’ve managed to do to me, kind sir. And, as I have already said, I am most greatful!

Yours truly,

Gregory Devine,

Saguenay, Quebec, Canada.

No RC records were burnt as they were not sent to the Four Courts. The only church who had to send them there was the Church of Ireland as it was the established church. 50% of their registers were lost. The other 50% either the minister “forgot” to send them or copied them inot books which they kept in the church