I’ve just finished reading Charles Townshend’s recently-published The Partition: Ireland Divided, 1885-1925 , which includes everything you could possibly want to know about the politics and violence that led to the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921. Like his masterwork Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion, (Penguin 2015), it’s lucid, meticulous and dispassionate. At times, he goes into a bit more detail of conversations between the likes of Lord Birkenhead and Andrew Bonar Law and Hamar Greenwood than most people would want to know. But if you do want to know, this is where to look.

I’ve just finished reading Charles Townshend’s recently-published The Partition: Ireland Divided, 1885-1925 , which includes everything you could possibly want to know about the politics and violence that led to the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921. Like his masterwork Easter 1916: The Irish Rebellion, (Penguin 2015), it’s lucid, meticulous and dispassionate. At times, he goes into a bit more detail of conversations between the likes of Lord Birkenhead and Andrew Bonar Law and Hamar Greenwood than most people would want to know. But if you do want to know, this is where to look.

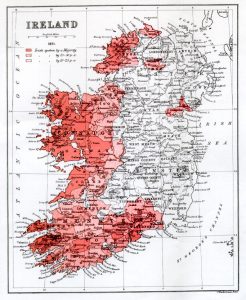

Slightly scary is the extent to which the pre-1921 era he describes mirrors our situation today. We’re currently having the same dialogue of the deaf, with Northern Unionists hearing every mention of a united Ireland as a threat to slaughter them in their beds and Southern (though not Northern) Nationalists blithely ignoring the fact that Unionism will never negotiate to unify the island.

As ever with Townshend, though, some of the most interesting parts of the book are the throwaway details. One that particularly caught my eye was a few sentences about the politicisation of the phrase “the Irish language” in the early 1900s.

When speaking to non-Irish audiences about Irish surnames, I repeatedly have to make the point that most of them have non-English-language origins in “Irish”. This is the name for the language used by everyone in Ireland today. But after saying it, to allay the puzzlement, I then have to add “by which I mean Gaelic”. For a long time, I’ve been mildly irritated by this: Would ye not bleddywell learn the difference between Ireland and Scotland and call the language by its proper name?

Townshend puts a stop to my gallop. Describing the Gaelic League (still its name today, note, not “The Irish League”), set up in 1893 as a non-sectarian, non-political organisation to promote and defend the language, he writes “Early in the new century, Gaelicists began to talk of ‘the Irish language’ rather than Gaelic, automatically (and deliberately) rendering those who did not speak it as less Irish and those who did not even acknowledge its status as non-Irish”. This may be over-simple. The language had been called “Irish” as well as “Gaelic” for centuries. But he’s right about the exclusionary implication in the carefully-coined phrase “the Irish language”: this is the (only) language of anyone who’s Irish. The League had been captured by Irish Irelanders using the language as a marker of national purity. That’s why “Irish” is now the standard term in Ireland (including Northern Ireland – I checked in the Belfast News Letter) and “Gaelic” has West Brit overtones.

Of course, if that vision of linguistic national purity had come about, I’d be writing this in Irish. And, to put it in Dublin English, I am in me Erse.

Hail Glorious Saint Patty.

Hi , ive been researching my heritage, I am a bit confused about this. My grandparents were from Ireland Cork I believe, My Mum was born in Glasgow and my Dad Liverpool. I guess we would be all mixed up. Just wondering how this works.Thanls.

For centuries, Irish people have left/leave Ireland for work opportunities that could not/cannot be found in Ireland. The Irish economy had improved significantly since the 1980s, except for the 2008 Great Recession and its prolonged aftermath. There were/are large historical Irish communities and significant Irish ancestry among the population of Great Britain, especially in London, Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester, etc. This made establishing and finding work in these locations easier.

And the exciting thing here with all this migrating is chain migration (not the convict type which in and of itself is a whole topic in itself) where unlike non Irish research you often have to go sideways to go backwards. Chain migration is for example Patrick O’Brien is sponsored by someone who is related to him and when he gets established, sponsors his brothet in law and so on. And when after they migrate in turn have other close relatives as Godparents etc

The best and most extensive Irish records come from outside of Ireland. Find every reference to Ireland from your non Irish sources as your starting point. Those in the know can then help you then make sense of and find any records in Ireland.

I too am one of those confused and mixed up by all this. My great grand father’s family came from a small town, Enagh, near Ballymoney in County Antrim. After he arrived in New York about 1845, he married a gal from Limerick. Some of their kids married Catholic and others Protestant. Maybe I should attribute this to America being known as the mixing pot of the world.

I have recently researched my ancestors from Knock And Bekan that moved here (Fitchburg, MA) and stayed together . My great grandmother was very hard to understand and had a heavy Irish accent. I have recently found out that the family kept their Irish culture, spoke Irish with each other and were often seen keening at wakes and funerals. Your blog has helped form a better picture and helps to recreate their life.

Hello John,

Thank you for your Posts – always enjoy and learn much and helps me start my day with a smile. My husband and I got hooked on the TV series Outlander, much of which is set in Scotland and most of the characters are Scottish and for the last four seasons I’ve had this question: Every episode, the Scottish characters speak some of the time in Gaelic, supposedly. How close then would their version of Gaelic be to my grandmother’s (b. 1867) who was from Darragh Glenroe, County Limerick? Could they have understood each other? If yes, could you tell us more in another blog about the origins of Gaelic and the tribes who ended up in Ireland, Wales and Scotland – and why not in England? Were they there originally only to be driven out by the Normans? I read a wonderful book several years ago and plan to reread it: Sea Kingdoms by Alistair Moffat: The History of Celtic Britain and Ireland. One of his points is that the peoples who inhabited the coastal areas of Ireland, Scotland, England, Wales, France, and other places accessible by water near there, had more in common than those residing 20 miles (or so) inland.

My Ulster Scots paternal line goes back, by Y-DNA testing, to the Causeway Coast of County Antrim (an historically and present-day majority Protestant area). My ancestor, born in the 1750s, was a staunch Covenater Presbyterian, turned up in America and, as would be expected, fought in the American Revolution for the Pennsylvania Rifles against the British. The ancestor of a cousin branch married, apparently for love, a Roman Catholic woman in 1820. Their children were baptized in the Catholic faith. One of them emigrated to American in 1852. That family, with an Ulster Scots surname in their midst, is Roman Catholic, on both sides of the Atlantic, to this day. Others of the same Ulster Scots surname, their Y-DNA ancestry (there are multiple Y-DNA lineages with the same surname) is unknown to me, were prominent Protestant Loyalists in the sectarian conflict and violence of the Troubles. So, it’s complicated, and not clear-cut.

The wretch wrapped in the Union flag and gazing towards England is sitting on my Gt Grandad in Co Wicklow. When I mention that my Thomas Mahoney came from Bray, I’m usually met with “So he was Protestant then”? No! He and all his family were catholic and as Irish as they come. No-one in Hindley, Lancs could tell a word he said and he’d lived there nearly 30 yrs. 🙂

Irish language – seems to have been the official term for the native tongue in Ireland … in the 1911 census folks were asked if they speak Irish

My great grandfather spoke Irish and I wish it had been passed on to us growing up here in the states. It was later emphasized that the language is “Irish” and not to be confused with “(Scottish) Gaelic”. Thank you for another enlightening blog John!

So what constitutes ‘Irish Music’ – That the words should be sung in Gaelic? Not Bono….

From my university days there as a musician I had a good friend who married a Detroit girl, so emigrated and founded the US folk band ‘Blackthorn’, and I remember discussing that issue

Gaeilge is the actual name of the language, itself derived from the ethnic designation of its speakers, na Gaeil. Same thing with most languages, which are called after the prime ethnicity which speaks it. Not the other way around! The English are so called not because that’s the name of their language but because their primary ethnic term, Anglecynne ‘English’, became the name of their language. Though they are still Sassanach ‘Saxons’ to us and as late as the 18th century, na Gaeil correctly called their language Saxbéarla. It was a sign of the times that a Gaelic term for language, béarla, became the term for the dominant Irish language of the past two hundred years, (Hiberno-)English.

Gaelic or Irish is fine, but frankly for several years now I’ve abandoned both in favour of Gaeilge. It helps to be specific and acquaint folk with the actual terms, and I have tried to do the same for all languages and ethnicities. Erse, of course, is not acceptable (as John implies!). It was a term in Scots/Albais for Gáidhlig, the Goidelic language spoken in the Isles, Scotland and northern England. though it was simply Scots for ‘Irish (language)’, it was used a very derogatory term because it sounds like ‘arse’.

Likewise, Gaelg is the language far better known by the English term, Manx. Gaeilge, Gáidhlig, Gaelg, Gaeilgeoir (speaker of Gaeilge), Gaeilgeoirí (speakers of Gaeilge), Gaelteacht, Gaelic, Goidelic, etc, all derive from the ethnic term. Gaeil came into use in the late Iron Age/early Medieval Era to denote the Connachta, the Eóghanachta, the Ciannachta and their allies in opposition to the Laigin and Ulaid. By the 850s it was the common ethnic term for all the Irish, including those in Britain and Mann.

Éirennach ‘Irish’ is the term which appears on Irish passports nowadays, first created back in the 15th century by the Gaelicised Anglo-Irish, na Gaill. It was their way of stressing that while they were not Gaeil, they too were of Ireland, and therefore Irish. It really caught on during the 17th century, when both Irish nations allied to oppose the English and Scots in Ireland.

In a hurry but just a few thoughts as I take a break on this lovely winter morning.

Seventy per cent of my cousins in Donegal speak Irish as their first language. My grandfather , died 1919, a prominent citizen, and a magistrate spoke Irish at home. His cousin, a high sheriff. spoke Irish. I know people of many different backgrounds with whom i have ever only spoken Irish. My Russian cousins the Breslin(ski)s understood Irish, and one of them has only ever spoken Irish to me and other members of my family. The exiled Gaelic elites in Europe spoke Irish as late as the beginning of the 19th century, a fact that that Habsburg monarchs were aware of and one of them . The present duke of Tetuan in Spain, Leopoldo O Donnell, when a child, was sent to Rannafast to learn Irish. Two years ago a member of the O Callaghan family in Catalunya asked me for Gaelic hymns and music for the expected funeral of her grandfather. In the eighteenth century members of the Gaelic gentry what was left of them spoke Irish and were patrons of poets and harpers. To be continued…

hi John . did you get my reply?

Hello again John. I always remember with pleasure our chats in the G.O. and now all that seems so long ago. Poetry and matters genealogical! When I first went abroad at the age of 19 many decades ago few people in France and Spain had ever heard of Ireland – Islandia , Hollanda, windmills, cold. Many of those who did know about us still regarded the Irish as English and it appears that most of them , especially in France, Spain and Italy still do. Et pourquoi? A friend of mine, a former ambassador, sometimes gave lectures on Irish literature when abroad, listing authors such as Swift, Goldsmith, Joyce and the usual suspects on one side of a blackboard, and after twenty minutes would write the names of Gaelic poets and prose writers from the 7th to the 21st century on the other, much to the surprise of audiences in English speaking countries, who at first wondered who these strange people were. I did the same type of thing,including speaking Irish, in my lectures in Australia and I could feel the sense of disbelief, and then the new found respect for who we are. The Paddy jokes usually stopped after I spoke.

To continue in the same vein. Fact : Irish literature in the Irish language is the oldest vernacular literature in Europe. Among its earliest works we have 7th century poems relating to the genealogies of the kings of Leinster and Munster, which bring the ancestors of contemporary persons mentioned back to the early 6th century. What we call the Irish genealogical corpus is the oldest collection of genealogies in Europe, spanning a period from the end of the 7th century to the 18th -always being expanded and being kept up to date, and all in irish -in the manuscript tradition. There is nothing like in Europe so take a bow. English families in Ireland are included.That tradition continues today as an oral one in Irish speaking areas where surnames are rarely used. There was a girl at school with me Maighread Shara Jack. Jack was Jack Phaidi Fheilimidh. Five generations heard in daily speech. Some of these Gaeltacht genealogies go back for seven generations. Feidhlimidh was the victim in Báidín Fheidhlimidh!