Most of the terrain of Irish genealogy is well mapped by now, with its familiar outlines of censuses, vital records, valuations and parish records, as well as the great smoking hole that is the 1922 destruction of the Public Record Office. But one area of the map remains stubbornly blank.

The Irish Land Commission was founded in 1881, initially to establish fair rents and then to break up estates and subsidise tenant purchase. In the thirty-five years before 1920, it oversaw the transfer of more than 13,500,000 acres. In the Free State it was reconstituted in 1923 and went on to acquire and distribute an additional 800,000 acres before it ceased acquiring land in 1983. It was finally dissolved in 1999. In Northern Ireland the Commission ceased new operations in 1925 and was abolished as part of the local government reforms of 1935.

The Irish Land Commission was founded in 1881, initially to establish fair rents and then to break up estates and subsidise tenant purchase. In the thirty-five years before 1920, it oversaw the transfer of more than 13,500,000 acres. In the Free State it was reconstituted in 1923 and went on to acquire and distribute an additional 800,000 acres before it ceased acquiring land in 1983. It was finally dissolved in 1999. In Northern Ireland the Commission ceased new operations in 1925 and was abolished as part of the local government reforms of 1935.

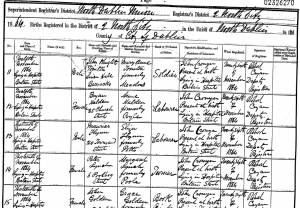

In the course of establishing title to the estates it was acquiring, the Commission collected an extraordinary cornucopia of material – wills, marriage settlements, title deeds, rentals, maps, pedigrees and more, often detailing families and their holdings back to the seventeenth century.

In Northern Ireland its records are all sensibly conserved and archived in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland – try searching the eCatalogue for the exact phrase “Land Commission” to get a sense of the sheer scale of what’s there.

And in the South? Nothing. The entire collection, now the property of the Dept of Agriculture, sits in a warehouse in Portlaoise under lock and key, uncatalogued, unconserved and harder to get at than the third secret of Fatima. The only publicly available records come in a list of the judicial decisions on fair rents, useful, but very limited.

During 35 years research, I’ve only met two people who have actually got access to the title records and one of them (full disclosure: a neighbour of mine) has just published a book using what he found.

Martin O’Halloran’s The Lost Gaeltacht: the Land Commission Migration – Clonbur, County Galway to Allenstown, Count Meath (Homefarm Publishing, Dublin 2020) is a painstaking and loving account of the Commission’s transfer of 24 families from an Irish-speaking community in Clonbur on the Galway/Mayo border to Allenstown in Meath in 1940. It was one of many social engineering projects undertaken by the De Valera government in the 1930s and 1940s, in this case attempting to seed the Irish language outside its existing home areas: Allenstown was officially designated Gaeltacht colony No. 5.

Martin O’Halloran’s The Lost Gaeltacht: the Land Commission Migration – Clonbur, County Galway to Allenstown, Count Meath (Homefarm Publishing, Dublin 2020) is a painstaking and loving account of the Commission’s transfer of 24 families from an Irish-speaking community in Clonbur on the Galway/Mayo border to Allenstown in Meath in 1940. It was one of many social engineering projects undertaken by the De Valera government in the 1930s and 1940s, in this case attempting to seed the Irish language outside its existing home areas: Allenstown was officially designated Gaeltacht colony No. 5.

Martin only got access because he had a direct legal link to the properties in the Commission records and even then he had a hard time. But he has managed to bring back an extraordinary haul: Maps, correspondence, disputes with Allenstown natives, with the Meath hunt, between the Commission and the Dept of Education. These are all woven carefully into a reconstruction of the community, its way of life and the great webs of extended kin-groups, in both Galway and Meath. This is the community Martin grew up in, and the whole story is tinged with poignancy. The Gaeltacht and its deep local culture were lost because of official neglect after the initial transplantation.

The book is essential reading not only for those with a connection to the locales covered, but for anyone with an interest in local history, the Land Commission, extended family history or indeed the possibilities of self-publication. Martin has produced a book the equal in quality of any of the multi-award-winning Cork University Press Atlases.

It’s available in-store in Hodges Figgis in Dublin, and online from Mayo Books.

One reason is that it’s been a while since I’ve done a fresh map from scratch. I’d forgotten how queasy heritage databases can be. Otto Von Bismarck is reputed to have said that you should never examine too closely how laws and sausages are made. The same holds true for looking at the entrails of heritage databases. Courtesy demands discretion, but just let’s say you shouldn’t expect to find too many surname matches for marriages in the Sligo parish of Emlefad and KIlmorgan.

One reason is that it’s been a while since I’ve done a fresh map from scratch. I’d forgotten how queasy heritage databases can be. Otto Von Bismarck is reputed to have said that you should never examine too closely how laws and sausages are made. The same holds true for looking at the entrails of heritage databases. Courtesy demands discretion, but just let’s say you shouldn’t expect to find too many surname matches for marriages in the Sligo parish of Emlefad and KIlmorgan.