A final round-up of sources to help track living relatives.

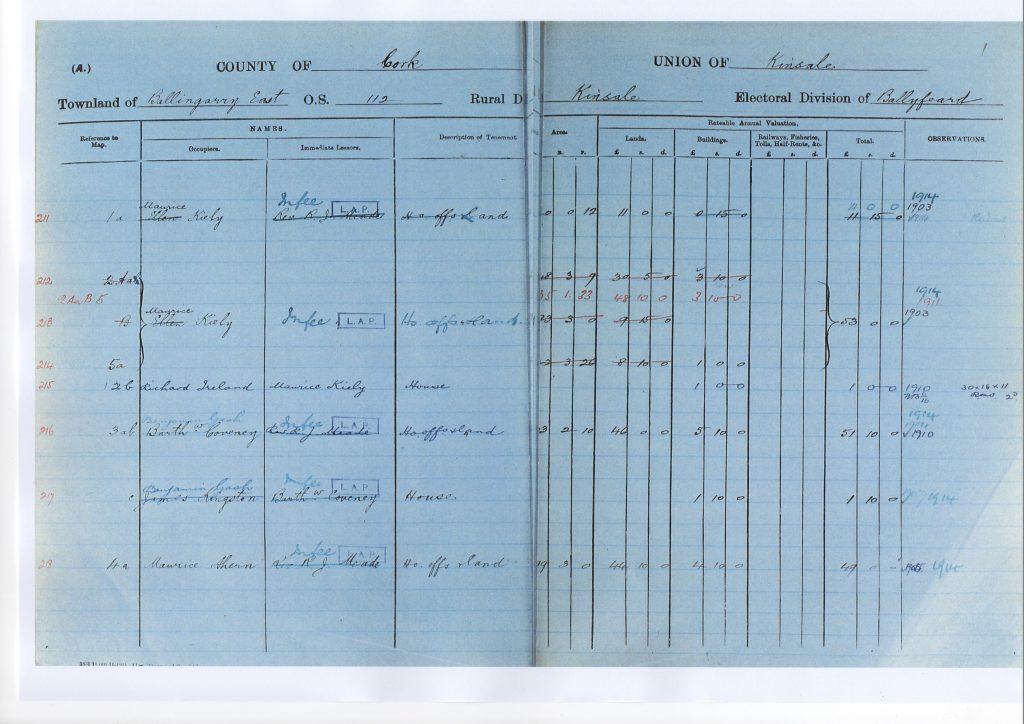

Most obvious are those that provide time-lapse records, with periodic snapshots of a family or place. Valuation Office revision books are the best example, but anything with recurring amendments can be useful, from used cheque-stubs to old football programmes. Below are some of the most useful.

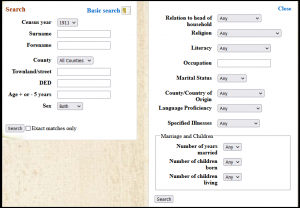

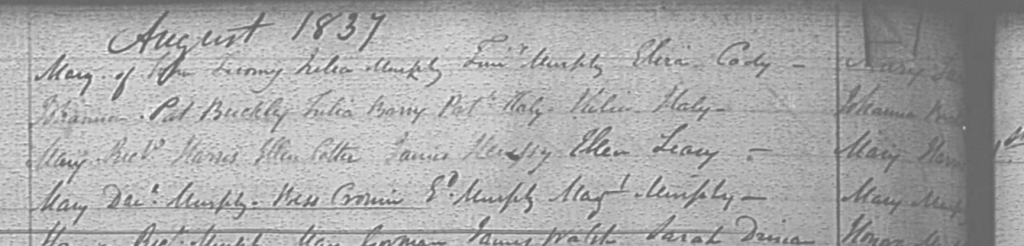

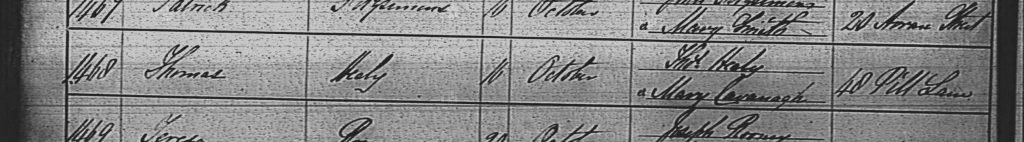

Voters lists: The right to vote was dependent on property and gender up to the middle of the nineteenth century. From the 1860s on, municipal and local authority elections began to broaden their constituencies until by the late 1890s local suffrage was wide enough to include working-class householders and (some) women. The only significant year-by-year collection is for Dublin city and is online at the Dublin City Library and Archive heritage database site. See this earlier blog post for more detail.

When (relatively) universal suffrage was introduced in 1918, annual voters lists became seriously useful. The biggest collection is again for Dublin city in DCLA and runs from 1938 to 1964. They used to be wonderfully searchable online at the DCLA site but a ludicrous kerfuffle about data protection means that the app is now only available onsite in the Reading Room. God forbid anyone should know where your granny lived in 1964. Hopefully common sense will eventually win out.

There are also more piecemeal undigitised collections in the National Archives, National Library and some county libraries. And the current register – www.checktheregister.ie – can be useful in confirming a family’s present location.

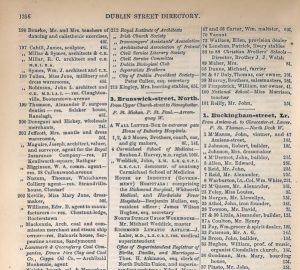

Urban street directories. From the late 1830s, annual Dublin directories included a street-by-street house-by-house listing of householders. Over the course of the following 190 years, coverage expanded and was revised for each year. The most comprehensive collection (and the easiest to follow year after year) is on open shelves in DCLA. There are excellent but incomplete online collections on Ancestry and askaboutireland. Much rummaging is required.

There are also good online collections of Belfast and Cork city directories. Unfortunately, they don’t have the regular year-to-year revisions of Dublin, but they’re still very useful.

Funeral notices: Funeral attendance is not optional in Ireland, even for the remotest of acquaintances. So a compulsory part of arranging a funeral is the newspaper death notice, which can include names, addresses, nephews, cemeteries … Notices became universal in the 1940s and full runs in national and local newspapers are online at www.irishnewsachive.com. Since 2006, www.rip.ie provides an online-only version.

DNA: One of the most common wrong-headed questions I’m regularly asked is whether there’s an Irish genealogy DNA-testing company. My answer is “Yes, of course. It’s called ancestry.com”.

So many Irish went to North America over the past century, and so many of their descendants have done Ancestry DNA tests, that probably 90% of the Irish national genome is already there. Find a relative who knows more than you (GEDmatch is also good) and bingo, you’re back in Ballydehob.

And if you need someone to disentangle your alleles from your centimorgans, there’s always the marvelous Dr. Maurice Gleeson.

The latest YouTube goes through all of this.