Since last week’s additions to IrishGenealogy’s birth, marriage and death records, I’ve been wallowing around in the site, as happy as a pig in … a toy-shop. I’ve spent almost all my working life dealing with these records, or rather fishing for them through the tiny keyhole provided by the printed indexes. Suddenly we’ve been handed the key itself.

There should be conga-lines of genealogists dancing down O’Connell Street.

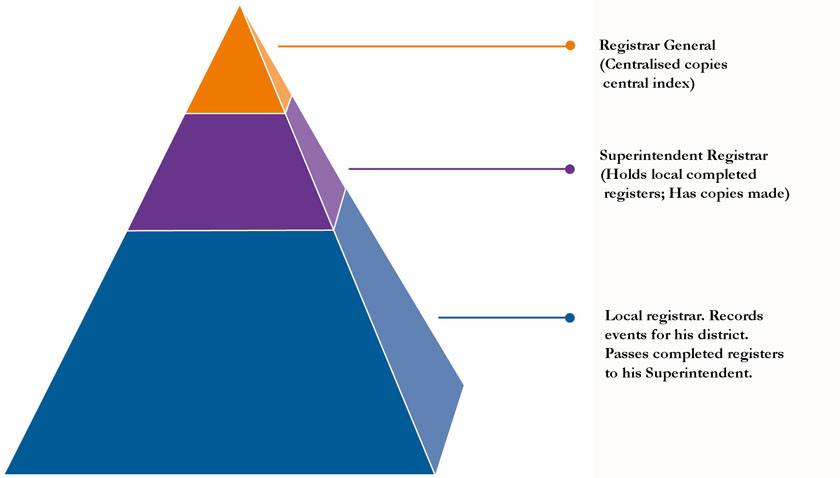

Some background: The General Register Office system for registering births, deaths and marriages in Ireland was (is) a perfect Victorian pyramid. The already-existing Poor Law Unions, catchment areas for a workhouse located in a large market town, were drafted in for double-duty to be used as the geographical basis of registration, and given the additional title “Superintendent Registrar’s District”. Most of them were already subdivided into local health areas, “Dispensary Districts”, which then also became “Registrar’s Districts”.

It was the job of the local registrar to record births and deaths (marriages were always a bit different) in pre-printed registers. Every three months these registers were passed to the Registrar’s boss, the Superintendent Registrar. He then had copies made of all the local registers and sent them to his superior, the top of the pyramid, the Registrar General.

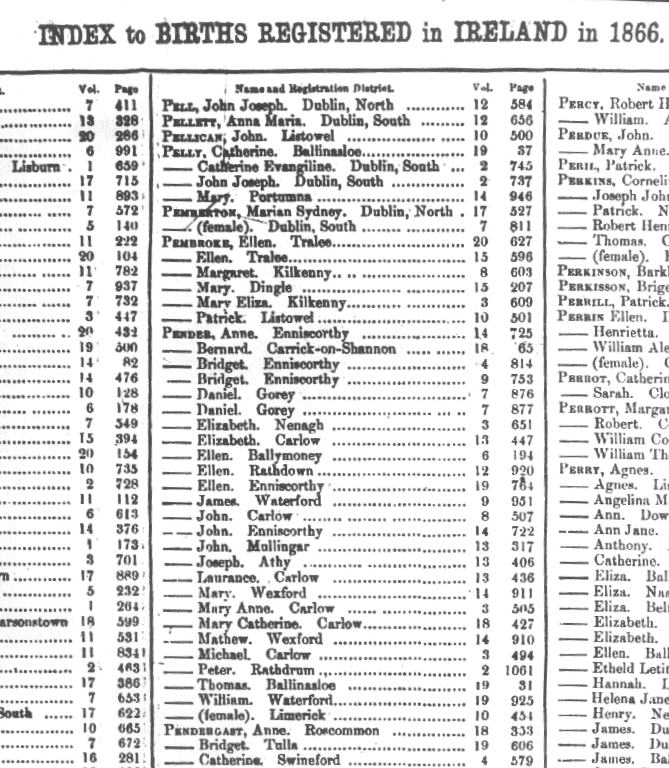

The Registrar General then had these copies indexed, producing printed indexes, covering births, deaths and marriages for the entire island, one volume per year until 1877, four per year thereafter. These are the indexes available in the General Register Office Search room in Dublin, until now, in theory at least, the only legal route of access to the historic registrations: the keyhole.

FamilySearch made a digital transcript of these indexes freely available more than five years ago, right up to 1958. In 2015, IrishGenealogy put up the GRO’s internal digital index (slightly more informative), but restricted to more than 100 years old for births, 75 for marriages and 50 for deaths.

What’s happened now is that IrishGenealogy has added online digital images of the copy-registers that its indexes point to. If you think your ancestor was one of the 25 John Murphy births registered in Kanturk Union between 1873 and 1876, up to now the only way to check full details of the entries was to buy print-outs of the images, a cool €100 in the case of the bould John. Now you can simply (and for nothing) click through each index entry and see full details: address, father’s occupation, mother’s maiden name …

Of course there are quibbles. Only the birth record images are complete. The marriage images start in 1882 and the deaths in 1891, so it’s still necessary to buy print-outs for marriages and deaths before those years. O and Mc surnames are treated very strangely in the indexes after 1900. The way the image digitisation was done makes it unnecessarily difficult (but not impossible) to reconstruct the local registrars’ records, an obvious treasure-trove for local historians. And some of the early registrations don’t seem to be imaged – Mary Scully in Abbeyleix Union in 1864 seems to have fallen between stools, for example. The FamilySearch transcript has much more information – an object lesson in the value of multiple transcripts.

But these are just tiny examples of that familiar occupational hazard, NGS, Nitpicking Genealogist Syndrome. What our Department of Arts, Heritage, Regional, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs has just done is simply extraordinary.

Ireland, a notorious black spot for family history less than a decade ago, is now a world leader in access to genealogical records.