Why are so many wonderful record-images beginning to appear on FamilySearch? The answer requires a long run-up …

Family history is an essential part of the practice of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, aimed at ensuring that everyone who has ever lived and who ever will live will ultimately be united in one great family tree. (Donald Akenson’s Some Family: The Mormons and How Humanity Keeps Track of Itself is a good, if slightly snide, account).

1813-1878. Not all Mormons were cuddly.

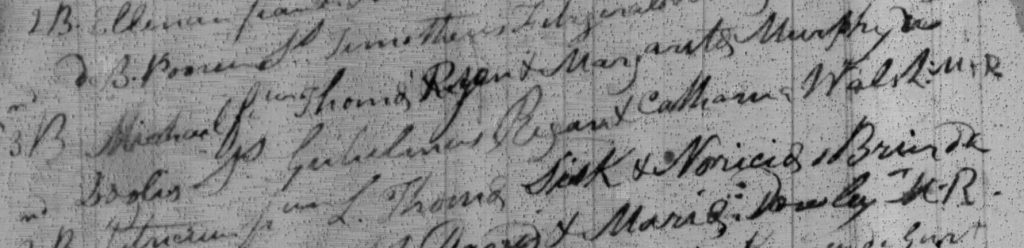

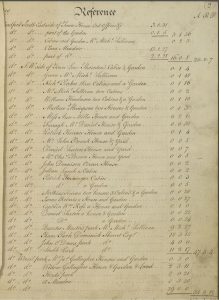

Because of this, the LDS have been collecting family history records since the 1890s and research in those records has been the main means of access to records for all family history researchers, Mormon and non-Mormon, for more than seventy years. Most Mormon temples have a Family History Centre that also opens to the public. Up to now, these Centres have depended on microfilm ordered via FamilySearch from the vast vaults of the Family History Library in Salt Lake City – their microfilms of the GRO registers are on open access in the Family History Centre in Dublin, for example.

Now that system is ending. From September 1st next, FamilySearch will discontinue its microfilm distribution services. The reason is simple: as microfilm declines in popularity the costs of storage and duplication have risen dramatically. In other words the internet killed it.

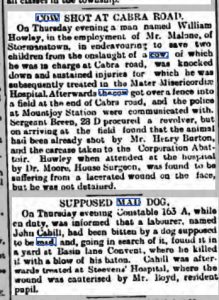

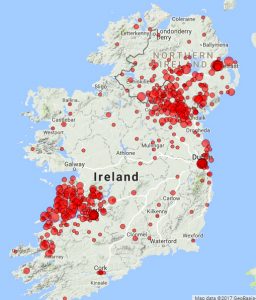

As a replacement FamilySearch promises that all its microfilm will be available as digital images. And that’s the reason for the tectonic shift we’ve been seeing recently in the availibility of Irish record images on the site: the Registry of Deeds, the GRO films, the Tithe survey, the National Archives testamentary collections and so much more. There is a simply a huge push on to get the films online before September.

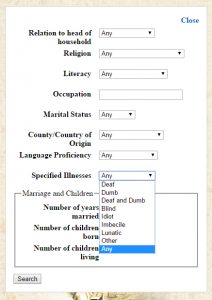

Unfortunately, access permissions haven’t yet been sorted out for many of the records. Click on that tantalising little camera icon and more often than not you’ll be told: ” These images are viewable: 1. To signed-in members of supporting organizations. 2. When using the site at a family history center.”

I enquired if I could sign up to be a supporting organisation (“I’ll be ever so supporting, I promise”) only to be told that there is currently only one supporting organisation: the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Personally, I’m delighted the microfilm is going. If they want someone to light the microfilm bonfire and dance around it, count me in. Thirty years spent squinting down microfilm readers has left me loathing the stuff.

Experience suggests that those viewing barriers will eventually melt. And in the meantime, I live quite close to the Dublin Family History Centre.