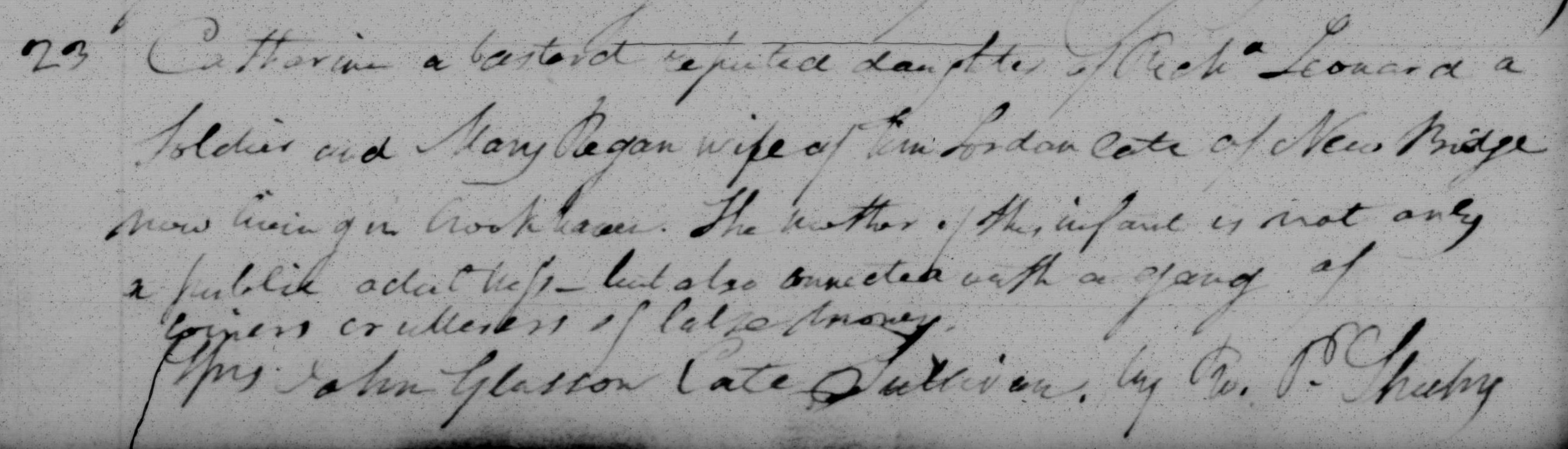

Received wisdom in Ireland has long been that the process of reclaiming and resuming the Gaelic patronymic prefixes “Mc” (mac, “son of”) and “Ó” (“grandson of”) paralleled the resurgence of interest in Gaelic culture in the second-half of the 19th century. In the words of Edward MacLysaght, “when the spirit of the nation revived”.

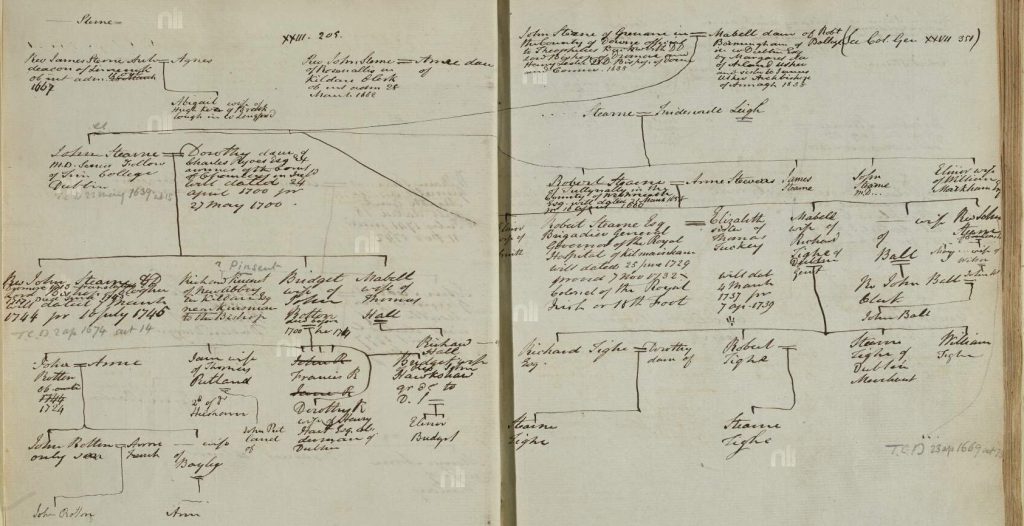

The process was never straightforward. Inevitably, some people mistakenly claimed the wrong prefix. The most notorious example is the Gaelic family Mac Gormáin – all are now either O’Gorman or plain Gorman. MacLysaght’s explanation of what happened still can’t be bettered:

“Probably the man chiefly responsible for the substitution of O for Mac in the name was the celebrated gigantic Chevalier Thomas O’Gorman (1725-1808), exiled vineyard owner in France who, after being ruined by the French Revolution, became a constructor of Irish pedigrees.”

Mistakes apart, the story told by MacLysaght and others about surname prefix resumption remains that of steady progress eventually flowering into independence.

The figures from birth registrations tell a different story.

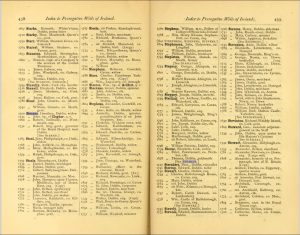

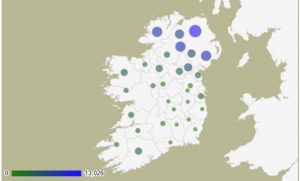

The proportion of total births recording Mc (or Mac, or M’) was 10.14 per cent in 1865. In 1913, it was 10.48 per cent. So there was a slow increase, but certainly nothing dramatic (see the chart here). It is tempting to surmise the great flood of “Mc” resumption only took off when it became clear in the early 1920s how useful a Gaelic-looking surname would be in the new Ireland.

Interestingly, the story is different for surnames starting “O'”.

In 1865, 1.67 per cent of total births used “O'”. By 1913, it was 3.2 per cent, almost doubling in five decades ( here). Perhaps the difference is that “O” surnames were found predominantly in Munster (and Donegal), traditionally nationalist regions, whereas “Mc” surnames were concentrated in north and east Ulster, with a solid unionist majority.

The devil remains where he always was, in the detail.