We’ve just done a big upgrade to the civil births maps, adding the 8 years 1914 to 1921, to match the civil deaths and marriages already covering those years. So three cheers, claps on the back, pints of shamrock all round. Except …

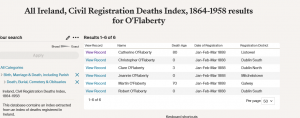

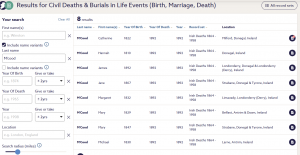

I thought the hair-raising LDS death and marriage transcriptions were the limit. No they weren’t.

Jhonston 1920

Johnnston 1915

Johnsron 1916

Johnstin 1914

Johsnton 1920

Or try:

Mujphy 1917

Murphu 1917

Murpjy 1921

Murpny 1915

Murpyy 1916

A number of demons are in play. First, from 1914 to 1918 many of the civil servants running the registration system were away at war. Those who took over seem to have had poor literacy skills, to put it kindly. Then from 1918 to 1921, came the War of Independence, with continual sabotage of all the existing (British) systems of administration, including the civil registration system. So there are plenty of good reasons why your ancestors’ birth, marriage or death might not be there.

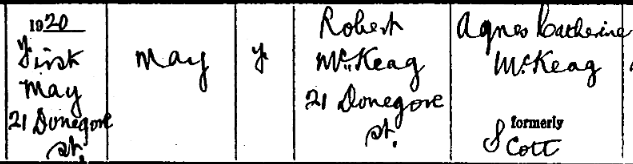

However, in the case of birth records from about 1911, there also seems to have been a bit of a breakdown in the transcription system used by IrishGenealogy. MAH MT KVAX born in Belfast in 1920? I don’t think so. If you look at the original, the child was May McKeag.

The only way a transcriber could have produced this is by trying to type with their head instead of their fingers. Banging their forehead off the keyboard, in other words.

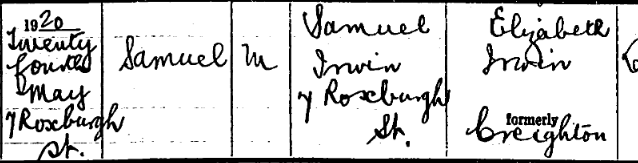

Whoever that poor suffering transcriber was, they left a trail of anguish: VUFARU MT TONNVLL; TACYVRZNV MAYONH ; BAMDVL ZRFZN.

The problems seem to be specific to IrishGenealogy births from about 1911 to 1921, so if you’re not finding a birth that should be there in that period, sweat other sources – FamilySearch, Rootsireland, the Northern Ireland GRO, even the printed indexes in the Dublin GRO search room.

Bamdvl Zrfzn, long-lost scion of the Irwins, I feel your pain.