Received wisdom in Ireland has long been that the process of reclaiming and resuming the Gaelic patronymic prefixes “Mc” (mac, “son of”) and “Ó” (“grandson of”) paralleled the resurgence of interest in Gaelic culture in the second-half of the 19th century. In the words of Edward MacLysaght, “when the spirit of the nation revived”.

The process was never straightforward. Inevitably, some people mistakenly claimed the wrong prefix. The most notorious example is the Gaelic family Mac Gormáin – all are now either O’Gorman or plain Gorman. MacLysaght’s explanation of what happened still can’t be bettered:

“Probably the man chiefly responsible for the substitution of O for Mac in the name was the celebrated gigantic Chevalier Thomas O’Gorman (1725-1808), exiled vineyard owner in France who, after being ruined by the French Revolution, became a constructor of Irish pedigrees.”

Mistakes apart, the story told by MacLysaght and others about surname prefix resumption remains that of steady progress eventually flowering into independence.

The figures from birth registrations tell a different story.

The proportion of total births recording Mc (or Mac, or M’) was 10.14 per cent in 1865. In 1913, it was 10.48 per cent. So there was a slow increase, but certainly nothing dramatic (see the chart here). It is tempting to surmise the great flood of “Mc” resumption only took off when it became clear in the early 1920s how useful a Gaelic-looking surname would be in the new Ireland.

Interestingly, the story is different for surnames starting “O'”.

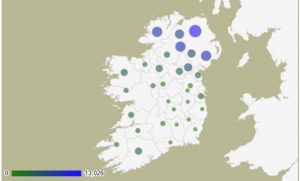

In 1865, 1.67 per cent of total births used “O'”. By 1913, it was 3.2 per cent, almost doubling in five decades ( here). Perhaps the difference is that “O” surnames were found predominantly in Munster (and Donegal), traditionally nationalist regions, whereas “Mc” surnames were concentrated in north and east Ulster, with a solid unionist majority.

The devil remains where he always was, in the detail.

Ancestors the Quillan s of Co Louth had become the McQuillans by 1864 and still are.

It would be interesting to know the percentage of Mc and O’ in bith the tithe applotment books and in Griffins. I know my GGrandfather was McGarrell when married in 1836 and his likely parent Daniel McGarrell died in 1813.

This certainly explains the mystery of why a Halloran family I was researching suddenly became O’Halloran on the headstone.

i am intriged by my surname of Fox grandfather from Kildare and Laurence first name very common in 1800,s .

the name Fox has no O or Mc anywhere why is this.

My “Neil” ancestors took their “O” back on the ship headed to America. We’ve been proud O’Neills ever since!

I’m an O’Neill myself!

My grandfather took back the “O” when he and my grandmother arrived in Melbourne, Australia, from Galway in 1914. Proudly he went from Donohue to O’Donoghue. Hence, my mother, born in Melbourne, had the birth name O’Donoghue.

But in civil registration, often the name was written down by someone paid by the Crown (up until Independence). The parents were often illiterate. So at a minimum it confounds an attempt to draw an inference about the Irish. More boldly, it supports a hypothesis that the explosion post-Independence resulted from removing biased scribes.

My great, great great great grandfather Nicholas Quinn and his son Matthew Quinn came from Dublin in 1776 to America. As far as I know there was no O before Quinn.

Mc/Mac have different origins from O’.

A large proportion of Mac/Mc names are of Scottish origin, while O’ is exclusively Irish. This explains why the proportion of Mc/Mac in 1913 did not vary much from 1865.

O’ is a different matter. From my own browsing of GRO indices and RC parish registers, it would appear that this prefix grew enormously from about 1880.

This probably was influenced by the economic meltdown accompanied by oppression, which characterised the decade from 1877. This induced people to decide that they were Irish rather than citizens of the UK. The cheapest and least dangerous way to express their Irishness, was to incorporate an O’, at least when their surnames could plausibly take it.

Thus Brien / O’Brien had been about 50/50, but by 1922 became 95/05 in favour of O’Brien. Neale / Neil also became largely O’Neill.

Of course, we have no way of knowing what individuals called themselves, only the variant chosen by the parish priest, dispensary doctor or Griffith’s valuator.

Thank you for this interesting article. I have no Irish ‘O’ surnames but do have Scottish ‘Mc/Mac’ surnames? What I would like to know is why the difference?

Jan

Very interesting. As far back into the 1800s as I have been able to determine, our name has been O’Neill but I wouldn’t be surprised to find a Neill in the past.

I am curious as to why my family was originally O Riada then changed to Reidy